Tales of Mystery and Imagination

Tales of Mystery and Imagination

" Tales of Mystery and Imagination es un blog sin ánimo de lucro cuyo único fin consiste en rendir justo homenaje a los escritores de terror, ciencia-ficción y fantasía del mundo. Los derechos de los textos que aquí aparecen pertenecen a cada autor.

Las imágenes han sido obtenidas de la red y son de dominio público. No obstante, si alguien tiene derecho reservado sobre alguna de ellas y se siente perjudicado por su publicación, por favor, no dude en comunicárnoslo.

Ángel Torres Quesada: Las pelotas que vinieron del espacio

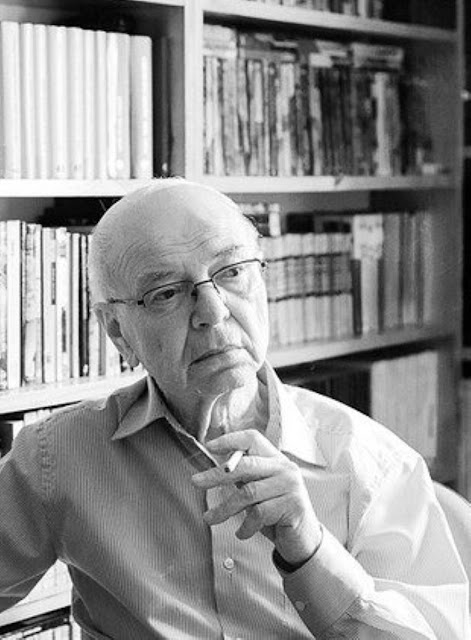

Algis Budrys: The War Is Over

Alfonso Álvarez Villar: Confusión en el hospital

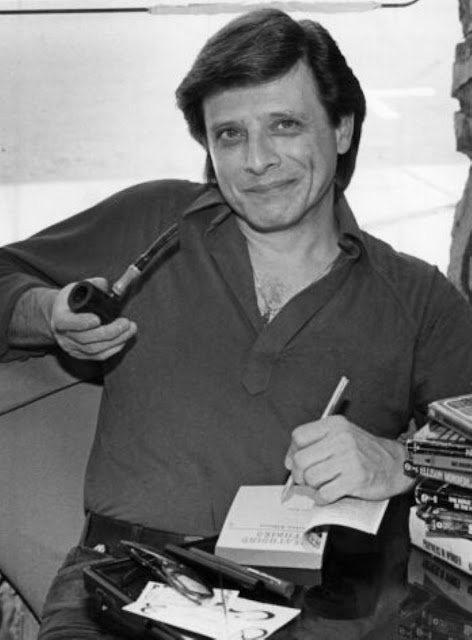

Harlan Ellison: Susan

Eduardo Vaquerizo: Una esfera perfecta

Hector Hugh Munro (Saki): Tobermory

It was a chill, rain-washed afternoon of a late August day, that indefinite season when partridges are still in security or cold storage, and there is nothing to hunt - unless one is bounded on the north by the Bristol Channel, in which case one may lawfully gallop after fat red stags. Lady Blemley's house-party was not bounded on the north by the Bristol Channel, hence there was a full gathering of her guests round the tea-table on this particular afternoon. And, in spite of the blankness of the season and the triteness of the occasion, there was no trace in the company of that fatigued restlessness which means a dread of the pianola and a subdued hankering for auction bridge. The undisguised open-mouthed attention of the entire party was fixed on the homely negative personality of Mr. Cornelius Appin. Of all her guests, he was the one who had come to Lady Blemley with the vaguest reputation. Some one had said he was "clever," and he had got his invitation in the moderate expectation, on the part of his hostess, that some portion at least of his cleverness would be contributed to the general entertainment. Until tea-time that day she had been unable to discover in what direction, if any, his cleverness lay. He was neither a wit nor a croquet champion, a hypnotic force nor a begetter of amateur theatricals. Neither did his exterior suggest the sort of man in whom women are willing to pardon a generous measure of mental deficiency. He had subsided into mere Mr. Appin, and the Cornelius seemed a piece of transparent baptismal bluff. And now he was claiming to have launched on the world a discovery beside which the invention of gunpowder, of the printing-press, and of steam locomotion were inconsiderable trifles. Science had made bewildering strides in many directions during recent decades, but this thing seemed to belong to the domain of miracle rather than to scientific achievement.

"And do you really ask us to believe," Sir Wilfrid was saying, "that you have discovered a means for instructing animals in the art of human speech, and that dear old Tobermory has proved your first successful pupil?"

"It is a problem at which I have worked for the last seventeen years," said Mr. Appin, "but only during the last eight or nine months have I been rewarded with glimmerings of success. Of course I have experimented with thousands of animals, but latterly only with cats, those wonderful creatures which have assimilated themselves so marvellously with our civilization while retaining all their highly developed feral instincts. Here and there among cats one comes across an outstanding superior intellect, just as one does among the ruck of human beings, and when I made the acquaintance of Tobermory a week ago I saw at once that I was in contact with a `Beyond-cat' of extraordinary intelligence. I had gone far along the road to success in recent experiments; with Tobermory, as you call him, I have reached the goal."

Mr. Appin concluded his remarkable statement in a voice which he strove to divest of a triumphant inflection. No one said "Rats," though Clovis's lips moved in a monosyllabic contortion which probably invoked those rodents of disbelief.

León Arsenal: Refutación de América

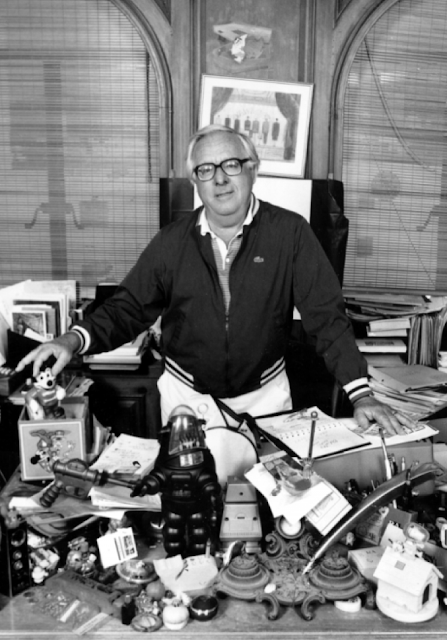

Ray Bradbury: The Highway

THE cooling afternoon rain had come over the valley, touching the corn in the tilled mountain fields, tapping on the dry grass roof of the hut. In the rainy darkness the woman ground corn between cakes of lava rock, working steadily. In the wet lightlessness, somewhere, a baby cried.

Hernando stood waiting for the rain to cease so he might take the wooden plow into the field again.

Below, the river boiled brown and thickened in its course. The concrete highway, another river, did not flow at all; it lay shining, empty. A car had not come along it in an hour. This was, in itself, of unusual interest. Over the years there had not been an hour when a car had not pulled up, someone shouting,

“Hey there, can we take your picture?” Someone with a box that clicked, and a coin in his hand. If he walked slowly across the field without his hat, sometimes they called, “Oh, we want you with your hat on!” And they waved their hands, rich with gold things that told time, or identified them, or did nothing at all but winked like spider’s eyes in the sun. So he would turn and go back to get his hat.

His wife spoke. “Something is wrong, Hernando?”

“Sí. The road. Something big has happened. Something big to make the road so empty this way.”

He walked from the hut slowly and easily, the rain washing over the twined shoes of grass and thick tire rubber he wore. He remembered very well the incident of this pair of shoes. The tire had come into the hut with violence one night, exploding the chickens and the pots apart! It had come alone, rolling swiftly.

The car, off which it had come, had rushed on, as far as the curve, and hung a moment, headlights reflected, before plunging into the river. The car was still there. One might see it on a good day, when the river ran slow and the mud cleared. Deep under, shining its metal, long and low and very rich, lay the car.

But then the mud came in again and you saw nothing.

The following day he had carved the shoe soles from the tire rubber.

He reached the highway now, and stood upon it, listening to the small sounds it made in the rain.

Then, suddenly, as if at a signal, the cars came. Hundreds of them, miles of them, rushing and rushing as he stood, by and by him. The big long black cars heading north toward the United States, roaring, taking the curves at too great a speed. With a ceaseless blowing and honking. And there was something about the faces of the people packed into the cars, something which dropped him into a deep silence. He stood back to let the cars roar on. He counted them until he tired. Five hundred, a thousand cars passed, and there was something in the faces of all of them. But they moved too swiftly for him to tell what this thing was.

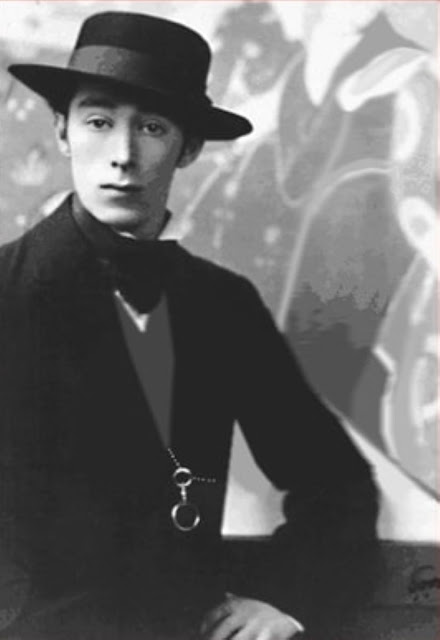

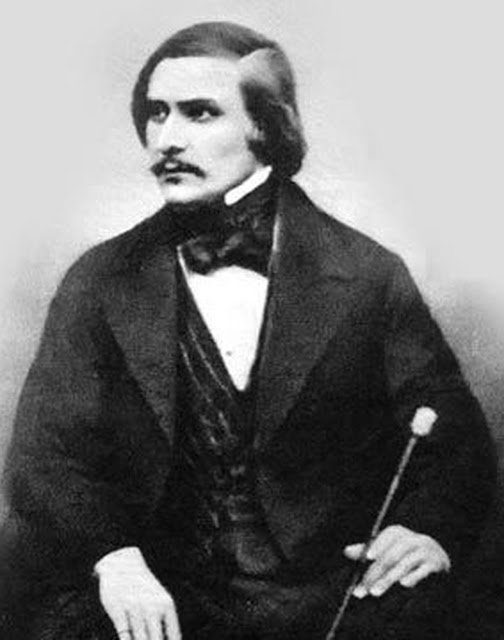

Nikolai Gogol ( Николай Васильевич Гоголь ): Viy ( Вий )

Salomé Guadalupe Ingelmo: La nueva raza

Lo

contrario del amor no es el odio, es la indiferencia. Lo contrario de la

belleza no es la fealdad, es la indiferencia. Lo contrario de la fe no es

herejía, es la indiferencia. Y lo contrario de la vida no es la muerte, sino la

indiferencia entre la vida y la muerte.

Elie Wiesel

El Sol se alza sobre un paisaje desolado, sobre los decadentes

restos de una civilización casi olvidada, de una humanidad extinta. Atraídas

por la promesa de calor, de entre los escombros surgen figuras de pequeña

estatura y pieles pálidas. Se asemejan vagamente a hombres, pero sus cuerpos lucen

huellas de impresionantes mutaciones.

Los dedos huesudos de nudillos prominentes revuelven

entre lo que, en otro tiempo, en otro mundo, se habría denominado “basura”.

Recogen la cabeza de una muñeca de cara sucia, ahora tuerta y medio calva. El

ser la sostiene a la altura de sus enormes ojos negros y escruta, en apariencia

conmovido, el iris azul de vidrio, solitario.

―Qué raza extraña la de los hombres. Unos desconocidos

hicieron del atesoramiento el objetivo principal de sus vidas y mira ahora…

Todos sus sueños terminaron aquí, en estos enormes montículos que se

descomponen bajo el sol. ¿Qué valor tenían sus ilusiones? Quién sabe cuánto

ansió alguien cada una de estas cosas ―dice con esa inconfundible forma de

hablar, entre jadeos, que los distingue―. Cuántas noches en vela proyectando

cómo conseguirlas, imaginando el placer que les habrían proporcionado…

―Esos hombres debían de ser muy estúpidos para luchar

entre sí por todos estos objetos inútiles. Sólo la comida puede dar la

felicidad. Sólo por ella vale la pena morir o matar.

El ser comprende que, pese a su juventud, el compañero

ha entendido ya: hambre y humanidad no son compatibles. Impresionado, lanza la

cabeza lejos y deposita la mano en su hombro para expresar de alguna forma lo

orgulloso que se siente de él.

El pequeño parece desconcertado y meditabundo. Observa

con insistencia la extremidad que reposa, inmóvil, cerca de su cuello, como una

araña exótica. Mira fijamente los peculiares dedos, aunque grotescos, especialmente

aptos para hurgar entre las montañas de restos. Deduce que su curiosa forma ha

de ser producto de una evolución en absoluto fortuita, de una estrategia bien

calculada por la naturaleza. Compara entonces esas manos con las suyas,

diminutas y rechonchas, y lo embargan la envidia y la ira.

Philip K. Dick: Roog

José María Aroca: Traidor

Pere Calders: La consciència, visitadora social