Durante la noche dejaba su dentadura en un vaso de agua hervida, sobre una mesita de caoba. Pues una noche, sigilosamente, la dentadura bajó al comedor y acabó todos los bizcochos.

Tales of Mystery and Imagination

Tales of Mystery and Imagination

" Tales of Mystery and Imagination es un blog sin ánimo de lucro cuyo único fin consiste en rendir justo homenaje a los escritores de terror, ciencia-ficción y fantasía del mundo. Los derechos de los textos que aquí aparecen pertenecen a cada autor.

Las imágenes han sido obtenidas de la red y son de dominio público. No obstante, si alguien tiene derecho reservado sobre alguna de ellas y se siente perjudicado por su publicación, por favor, no dude en comunicárnoslo.

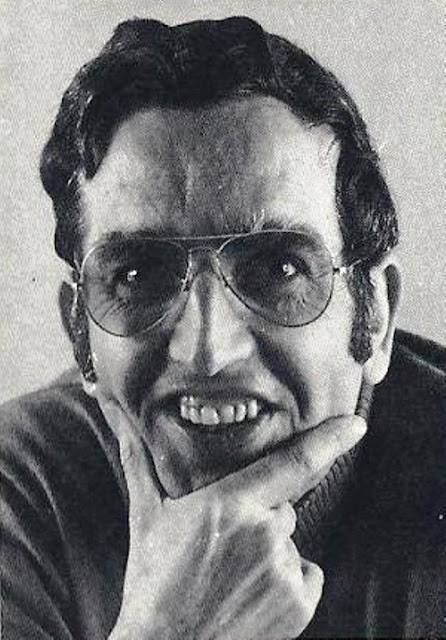

Juan Carlos Onetti: La escopeta

No era noche cerrada cuando estiré el brazo para encender la lámpara sobre la mesa. Era necesario que terminara de escribir mi artículo antes del alba y correr para echarlo al buzón y esperar acurrucado que volviera el cartero entre la bruma que el amanecer iba castigando con látigo del color exacto de la sangre fresca y brillante. Volvía muy gordo y tranquilo trayéndome el cheque mensual y era necesario apurarse y no fue más que encender la luz y oír el ruido de alguien tratando de forzar la cerradura y alrededor de mí la soledad de la aldea desierta, inmovilizada por la luna vertical justo en el centro geométrico del mundo tan inmenso con tantos millones de camas donde balbuceaban sus sueños personas diversas y dormidas, cada una con un hilo de baba rozando las mejillas y estirándose con dibujos raros en la blancura de las almohadas. Hasta que salté y me puse a un costado de la puerta preguntando muchas veces con un ritmo invariable quién es, qué quiere, qué busca. Y un silencio y el forcejeo rodeó la casita y continuó trabajando en una de las ventanas no recuerdo cual, impulsándome en dos movimientos sucesivos, casi sin pausa, a matar con la palma de la mano la luz de la mesa y abrir el armario para sacar la escopeta y luego caminando de una ventana a otra y de una ventana a la puerta, según variaban los ruidos del ladrón, siempre preguntando hasta la ronquera qué busca, haciendo girar la escopeta, oliendo crecer desde el pecho y las axilas el olor tenebroso del miedo y la fatalidad.

Después de una pausa y un pequeño ruido de papeles, el hombre de la baba blanca habló detrás de mi nuca. Su voz era átona:

-Este sí que es fácil. Un sueño elemental. Hasta un niño podría interpretarlo. Yo soy el ladrón que busca saber, entrar en su ego. ¿Por qué tanto miedo?

Edith Wharton: The Lady's Maid's Bell

I

IT WAS the autumn after I had the typhoid. I'd been three months in hospital, and when I came out I looked so weak and tottery that the two or three ladies I applied to were afraid to engage me. Most of my money was gone, and after I'd boarded for two months, hanging about the employment agencies, and answering any advertisement that looked any way respectable, I pretty nearly lost heart, for fretting hadn't made me fatter, and I didn't see why my luck should ever turn. It did though--or I thought so at the time. A Mrs. Railton, a friend of the lady that first brought me out to the States, met me one day and stopped to speak to me: she was one that had always a friendly way with her. She asked me what ailed me to look so white, and when I told her, "Why, Hartley," says she, "I believe I've got the very place for you. Come in to-morrow and we'll talk about it."

The next day, when I called, she told me the lady she'd in mind was a niece of hers, a Mrs. Brympton, a youngish lady, but something of an invalid, who lived all the year round at her country-place on the Hudson, owing to not being able to stand the fatigue of town life.

"Now, Hartley," Mrs. Railton said, in that cheery way that always made me feel things must be going to take a turn for the better--"now understand me; it's not a cheerful place I'm sending you to. The house is big and gloomy; my niece is nervous, vaporish; her husband--well, he's generally away; and the two children are dead. A year ago I would as soon have thought of shutting a rosy active girl like you into a vault; but you're not particularly brisk yourself just now, are you? and a quiet place, with country air and wholesome food and early hours, ought to be the very thing for you. Don't mistake me," she added, for I suppose I looked a trifle downcast; "you may find it dull but you won't be unhappy. My niece is an angel. Her former maid, who died last spring, had been with her twenty years and worshiped the ground she walked on. She's a kind mistress to all, and where the mistress is kind, as you know, the servants are generally good-humored, so you'll probably get on well enough with the rest of the household. And you're the very woman I want for my niece: quiet, well-mannered, and educated above your station. You read aloud well, I think? That's a good thing; my niece likes to be read to. She wants a maid that can be something of a companion: her last was, and I can't say how she misses her. It's a lonely life.... Well, have you decided?"

"Why, ma'am," I said, "I'm not afraid of solitude."

"Well, then, go; my niece will take you on my recommendation. I'll telegraph her at once and you can take the afternoon train. She has no one to wait on her at present, and I don't want you to lose any time."

I was ready enough to start, yet something in me hung back; and to gain time I asked, "And the gentleman, ma'am?"

"The gentleman's almost always away, I tell you," said Mrs. Railton, quick-like--"and when he's there," says she suddenly, "you've only to keep out of his way."

Salomé Guadalupe Ingelmo: El duende que tuvo que crecer

Observa extasiado la armoniosa danza de las patatas que pilpilean en la lumbre. Es consciente de que sin las tradiciones él no sería nada, y sospecha que dentro de no mucho tiempo, cuando los jóvenes hayan olvidado por completo el pasado y las costumbres de su tierra y los viejos ya no tengan cabeza para podérselas recordar, morirá definitivamente. Por eso se obstina en seguir cociendo las patatas lentamente, muy lentamente, en olla de barro y sobre las brasas del hogar. Los modestos tubérculos canturrean su monótono “chup, chup” tímidamente. Su suave gorjeo se convierte en un arrullo para el anciano que duerme en la habitación contigua.

El duende remueve delicadamente el contenido de la olla con una cuchara de madera y se lleva un poco a la enorme boca, en la que siempre parece pintarse un gesto risueño y un poco travieso. Mientras degusta con glotonería la sencilla vianda, sonríe satisfecho. Las patatas casi están en su punto. Dentro de muy poco adquirirán la textura melosa que tanto gusta a su anfitrión. Entonces podrá retirarlas del fuego y dejarlas al amor de la lumbre para que se mantengan calientes hasta que se levante y decida comer.

Se considera un buen cocinero, pero aún así recuerda con nostalgia los tiempos en los que la esposa del anciano preparaba galletas y pasteles de los que él daba buena cuenta por las noches.

―¡Ajá! Te pillé, bicho del demonio.

El inesperado fogonazo de luz coge por sorpresa al duende, que esta vez no ha oído llegar a la sigilosa propietaria de la casa. Evidentemente ya es demasiado tarde para escabullirse de un salto, de modo que no se le ocurre nada mejor que seguir royendo su botín a dos carrillos. Se introduce las galletas en la boca a gran velocidad, sin darse siquiera el tiempo de tragarlas, hasta que sus hinchados mofletes son incapaces de albergar ni un pedacito más de dulce.

Cuando el esposo de la encolerizada repostera llega a la cocina bostezando y frotándose los ojos, encuentra un pequeño hombrecillo sentado en el suelo. La criatura custodia el bote en el que su mujer suele guardar las galletas entre las escuálidas piernas, lo abraza tiernamente. Su juboncillo rojo está lleno de migas. Cuando el pequeño ser intenta lanzarle una sonrisa entre tímida y avergonzada, algunos pedazos de galleta se le escapan entre los labios.

―¡Qué desfachatez! No sólo se pasa la noche haciendo ruido, sino que además se come nuestro desayuno.

El diminuto trasgo parece arrepentido. Agacha sus enormes y puntiagudas orejas como haría un perro cogido en falta. Sus ojillos negros y vivaces evitan los de los irritados humanos.

―Y tú, Manuel, ¿acaso no le vas a decir nada?

―Por supuesto ―responde con desgana, interesado únicamente en zanjar lo antes posible la conversación para poder volver a la cama―. Muchacho, la próxima vez procura tomarte las galletas con un vaso de leche para ayudarlas a bajar. Así no se te quedarán atascadas en el gañote ―sugiere al duendecillo, que le observa aliviado y agradecido mientras recoge concienzudamente las últimas migajas desperdigadas sobre su ropa y se las introduce como buenamente puede en la boca llena.

Manuel se dirige de nuevo hacia la alcoba arrastrando pesadamente los pies. Atrás quedan los reproches de su airada esposa, que ahora parece más enfadada con él que con el propio intruso.

Steven Millhauser: Eisenheim the Illusionist

In the last years of the nineteenth century, when the Empire of the Hapsburgs was nearing the end of its long dissolution, the art of magic flourished as never before. In obscure villages of Moravia and Galicia, from the Istrian Peninsula to the mists of Bukovina, bearded and black-caped magicians in market squares astonished townspeople by drawing streams of dazzling silk handkerchiefs from empty paper cones, removing billiard balls from children's ears, and throwing into the air decks of cards that assumed the shapes of fountains, snakes, and angels before returning to the hand. In cities and larger towns, from Zagreb to Lvov, from Budapest to Vienna, on the stages of opera houses, town halls, and magic theaters, traveling conjurers equipped with the latest apparatus enchanted sophisticated audiences with elaborate stage illusions. It was the age of levitations and decapitations, of ghostly apparitions and sudden vanishings, as if the tottering Empire were revealing through the medium of its magicians its secret desire for annihilation. Among the remarkable conjurers of that time, none achieved the heights of illusion attained by Eisenheim, whose enigmatic final performance was viewed by some as a triumph of the magician's art, by others as a fateful sign.

Eisenheim, né Eduard Abramowitz, was born in Bratislava in 1859 or 1860. Little is known of his early years, or indeed of his entire life outside the realm of illusion. For the scant facts we are obliged to rely on the dubious memoirs of magicians, on comments in contemporary newspaper stories and trade periodicals, on promotional material and brochures for magic acts; here and there the diary entry of a countess or ambassador records attendance at a performance in Paris, Cracow, Vienna. Eisenheim's father was a highly respected cabinetmaker, whose ornamental gilt cupboards and skillfully carved lowboys with lion-paw feet and brass handles shaped like snarling lions graced the halls of the gentry of Bratislava. The boy was the eldest of four children; like many Brarislavan Jews, the family spoke German and called their city Pressburg, although they understood as much Slovak and Magyar as was necessary for the proper conduct of business. Eduard went to work early in his father's shop. For the rest of his life he would retain a fondness for smooth pieces of wood joined seamlessly by mortise and tenon. By the age of seventeen he was himself a skilled cabinetmaker, a fact noted more than once by fellow magicians who admired Eisenheim's skill in constructing trick cabinets of breathtaking ingenuity. The young craftsman was already a passionate amateur magician, who is said to have entertained family and friends with card sleights and a disappearing-ring trick that required a small beechwood box of his own construction. He would place a borrowed ring inside, fasten the box tightly with twine, and quietly remove the ring as he handed the box to a spectator. The beechwood box, with its secret panel, was able to withstand the most minute examination.

A chance encounter with a traveling magician is said to have been the cause of Eisenheim's lifelong passion for magic. The story goes that one day, returning from school, the boy saw a man in black sitting under a plane tree. The man called him over and lazily, indifferently, removed from the boy's ear first one coin and then another, and then a third, coin after coin, a whole handful of coins, which suddenly turned into a bunch of red roses. From the roses the man in black drew out a white billiard ball, which turned into a wooden flute that suddenly vanished. One version of the story adds that the man himself then vanished, along with the plane tree. Stories, like conjuring tricks, are invented because history is inadequate to our dreams, but in this case it is reasonable to suppose that the future master had been profoundly affected by some early experience of conjuring. Eduard had once seen a magic shop, without much interest; he now returned with passion. On dark winter mornings on the way to school he would remove his gloves to practice manipulating balls and coins with chilled fingers in the pockets of his coat. He enchanted his three sisters with intricate shadowgraphs representing Rumpelstiltskin and Rapunzel, American buffaloes and Indians, the golem of Prague. Later a local conjurer called Ignazc Molnar taught him juggling for the sake of coordinating movements of the eye and hand. Once, on a dare, the thirteen-year-old boy carried an egg on a soda straw all the way to Bratislava Castle and back. Much later, when all this was far behind him, the Master would be sitting gloomily in the corner of a Viennese apartment where a party was being held in his honor, and reaching up wearily he would startle his hostess by producing from the air five billiard balls that he proceeded to juggle flawlessly.

Horacio Quiroga: Las medias de los flamencos

Cierta vez las víboras dieron un gran baile. Invitaron a las ranas y a los sapos, a los flamencos, y a los yacarés y a los peces. Los peces, como no caminan, no pudieron bailar; pero siendo el baile a la orilla del río, los peces estaban asomados a la arena, y aplaudían con la cola.

Los yacarés, para adornarse bien, se habían puesto en el pescuezo un collar de plátanos, y fumaban cigarros paraguayos. Los sapos se habían pegado escamas de peces en todo el cuerpo, y caminaban meneándose, como si nadaran. Y cada vez que pasaban muy serios por la orilla del río, los peces les gritaban haciéndoles burla.

Las ranas se habían perfumado todo el cuerpo, y caminaban en dos pies. Además, cada una llevaba colgada, como un farolito, una luciérnaga que se balanceaba.

Pero las que estaban hermosísimas eran las víboras. Todas, sin excepción, estaban vestidas con traje de bailarina, del mismo color de cada víbora. Las víboras coloradas llevaban una pollerita de tul colorado; las verdes, una de tul verde; las amarillas, otra de tul amarillo; y las yararás, una pollerita de tul gris pintada con rayas de polvo de ladrillo y ceniza, porque así es el color de las yararás.

Y las más espléndidas de todas eran las víboras de que estaban vestidas con larguísimas gasas rojas, y negras, y bailaban como serpentinas Cuando las víboras danzaban y daban vueltas apoyadas en la punta de la cola, todos los invitados aplaudían como locos.

Sólo los flamencos, que entonces tenían las patas blancas, y tienen ahora como antes la nariz muy gruesa y torcida, sólo los flamencos estaban tristes, porque como tienen muy poca inteligencia, no habían sabido cómo adornarse. Envidiaban el traje de todos, y sobre todo el de las víboras de coral. Cada vez que una víbora pasaba por delante de ellos, coqueteando y haciendo ondular las gasas de serpentinas, los flamencos se morían de envidia.

Un flamenco dijo entonces:

—Yo sé lo que vamos a hacer. Vamos a ponernos medias coloradas, blancas y negras, y las víboras de coral se van a enamorar de nosotros.

Y levantando todos juntos el vuelo, cruzaron el río y fueron a golpear en un almacén del pueblo.

—¡Tan-tan! —pegaron con las patas.

—¿Quién es? —respondió el almacenero.

—Somos los flamencos. ¿Tiene medias coloradas, blancas y negras?

—No, no hay —contestó el almacenero—. ¿Están locos? En ninguna parte van a encontrar medias así. Los flamencos fueron entonces a otro almacén.

—¡Tan-tan! ¿Tienes medias coloradas, blancas y negras?

El almacenero contestó:

—¿Cómo dice? ¿Coloradas, blancas y negras? No hay medias así en ninguna parte. Ustedes están locos. ¿quiénes son?

Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu: The white cat of Drumgunniol

There is a famous story of a white cat, with which we all become acquainted in the nursery. I am going to tell a story of a white cat very different from the amiable and enchanted princess who took that disguise for a season. The white cat of which I speak was a more sinister animal.

The traveller from Limerick toward Dublin, after passing the hills of Killaloe upon the left, as Keeper Mountain rises high in view, finds himself gradually hemmed in, up the right, by a range of lower hills. An undulating plain that dips gradually to a lower level than that of the road interposes, and some scattered hedgerows relieve its somewhat wild and melancholy character.

One of the few human habitations that send up their films of turf-smoke from that lonely plain, is the loosely-thatched, earth-built dwelling of a "strong farmer," as the more prosperous of the tenant-farming classes are termed in Munster. It stands in a clump of trees near the edge of a wandering stream, about half-way between the mountains and the Dublin road, and had been for generations tenanted by people named Donovan.

In a distant place, desirous of studying some Irish records which had fallen into my hands, and inquiring for a teacher capable of instructing me in the Irish language, a Mr. Donovan, dreamy, harmless, and learned, was recommended to me for the purpose.

I found that he had been educated as a Sizar in Trinity College, Dublin. He now supported himself by teaching, and the special direction of my studies, I suppose, flattered his national partialities, for he unbosomed himself of much of his long-reserved thoughts, and recollections about his country and his early days. It was he who told me this story, and I mean to repeat it, as nearly as I can, in his own words.

I have myself seen the old farm-house, with its orchard of huge mossgrown apple trees. I have looked round on the peculiar landscape; the roofless, ivied tower, that two hundred years before had afforded a refuge from raid and rapparee, and which still occupies its old place in the angle of the haggard; the bush-grown "liss," that scarcely a hundred and fifty steps away records the labours of a bygone race; the dark and towering outline of old Keeper in the background; and the lonely range of furze and heath-clad hills that form a nearer barrier, with many a line of grey rock and clump of dwarf oak or birch. The pervading sense of loneliness made it a scene not unsuited for a wild and unearthly story. And I could quite fancy how, seen in the grey of a wintry morning, shrouded far and wide in snow, or in the melancholy glory of an autumnal sunset, or in the chill splendour of a moonlight night, it might have helped to tone a dreamy mind like honest Dan Donovan's to superstition and a proneness to the illusions of fancy. It is certain, however, that I never anywhere met with a more simple-minded creature, or one on whose good faith I could more entirely rely.

Alberto Chimal: La vista fija

Érase una niña pequeñita y muy bonita, con chapas rojas rojas cual flores de rubor, vestidito rosa y bonito cabello rizado. Jugaba en un parque con su pelota y era muy feliz. Oyóse entonces un disparo, y la frente de la niña hizo ¡pop!, y una emisión hubo de sangre y sesos entremezclados que, flor también de rubor (aunque de otro, ¡ay, de otro rubor!), cayó en el pasto un segundo o dos antes que la propia niña.

De la pelota no se supo más, y yo creo que alguien se la robó. Debe haber sido fácil porque hasta la niña, que no se movía y de cuya frente seguía manando ese caldo rojo y tremebundo, llegó una mujer que pants que se quedó con la vista fija en ella; un señor de traje barato que también se quedó con la vista fija en ella; un par de muchachos, con uniforme y peinados de escuela militarizada, que también se quedaron con la vista fija en ella.

Y una anciana de coche con chofer, su chofer, un grupo de novicias, tres policías, un comerciante informal, un malabarista de crucero, un ejecutivo de exitosa empresa y otros muchos más, hombres y mujeres, jóvenes y viejos, que tras llegar se quedaron igualmente alrededor de la niña, igualmente con la vista fija en ella, arruinando con sus pies descuidados el pasto del parque, favoreciendo la huida del posible y desalmado ladrón de pelotas, presas todos de la misma atracción: del mismo embrujo, imperioso y extraño.

Porque no se encontraban ante un televisor, no había reportero que comentara lo que veían, no se veía logotipo ni anuncio superpuesto ni nada entre ellos y las manchas rojas rojas en el pasto verde, los rizos manchados de rojo, los trozos de cráneo igualmente manchados de rojo, la expresión de sorpresa en la carita infantil, los bracitos y piernitas inertes, laxos, ya fríos.

Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Great Stone Face

One afternoon, when the sun was going down, a mother and her little boy sat at the door of their cottage, talking about the Great Stone Face. They had but to lift their eyes, and there it was plainly to be seen, though miles away, with the sunshine brightening all its features.

And what was the Great Stone Face?

Embosomed amongst a family of lofty mountains, there was a valley so spacious that it contained many thousand inhabitants. Some of these good people dwelt in log-huts, with the black forest all around them, on the steep and difficult hill-sides. Others had their homes in comfortable farm-houses, and cultivated the rich soil on the gentle slopes or level surfaces of the valley. Others, again, were congregated into populous villages, where some wild, highland rivulet, tumbling down from its birthplace in the upper mountain region, had been caught and tamed by human cunning, and compelled to turn the machinery of cotton-factories. The inhabitants of this valley, in short, were numerous, and of many modes of life. But all of them, grown people and children, had a kind of familiarity with the Great Stone Face, although some possessed the gift of distinguishing this grand natural phenomenon more perfectly than many of their neighbors.

The Great Stone Face, then, was a work of Nature in her mood of majestic playfulness, formed on the perpendicular side of a mountain by some immense rocks, which had been thrown together in such a position as, when viewed at a proper distance, precisely to resemble the features of the human countenance. It seemed as if an enormous giant, or a Titan, had sculptured his own likeness on the precipice. There was the broad arch of the forehead, a hundred feet in height; the nose, with its long bridge; and the vast lips, which, if they could have spoken, would have rolled their thunder accents from one end of the valley to the other. True it is, that if the spectator approached too near, he lost the outline of the gigantic visage, and could discern only a heap of ponderous and gigantic rocks, piled in chaotic ruin one upon another. Retracing his steps, however, the wondrous features would again be seen; and the farther he withdrew from them, the more like a human face, with all its original divinity intact, did they appear; until, as it grew dim in the distance, with the clouds and glorified vapor of the mountains clustering about it, the Great Stone Face seemed positively to be alive.

It was a happy lot for children to grow up to manhood or womanhood with the Great Stone Face before their eyes, for all the features were noble, and the expression was at once grand and sweet, as if it were the glow of a vast, warm heart, that embraced all mankind in its affections, and had room for more. It was an education only to look at it. According to the belief of many people, the valley owed much of its fertility to this benign aspect that was continually beaming over it, illuminating the clouds, and infusing its tenderness into the sunshine.

As we began with saying, a mother and her little boy sat at their cottage-door, gazing at the Great Stone Face, and talking about it. The child's name was Ernest.

"Mother," said he, while the Titanic visage smiled on him, "I wish that it could speak, for it looks so very kindly that its voice must needs be pleasant. If I were to see a man with such a face, I should love him dearly."

"If an old prophecy should come to pass," answered his mother, "we may see a man, some time or other, with exactly such a face as that."

"What prophecy do you mean, dear mother?" eagerly inquired Ernest. "Pray tell me about it!"

Jesús Díaz: El polvo a la mitad

Una película de polvo lo había cubierto todo, desde el auto hasta nuestro pelo. Habíamos cerrado los cristales, pero el polvo cubría los asientos. No hablábamos, pero nos abrasaba las gargantas. Hacía rato que ni los animales ni los campos tenían color, sólo el polvo. Hacía rato también que el terraplén no se distinguía del resto del campo. El campo todo era un inmenso terraplén con una persistente nube de polvo que no acaba de ascender; se mantenía fija, larga, pegada al camino y a todo cuanto pasaba por el camino que era todo lo que había allí, porque todo era igual, todo terraplén, y todo el terraplén era polvo. Lo otro era el sol. Un sol sin centro ni rayos, un sol esparcido, un sol solo calor. Calor, aquel sol no poseía otro atributo. Lo demás éramos nosotros. Intenté mirar la hora para saber el tiempo que nos faltaba de camino, y el tiempo que llevábamos por aquel terraplén, pero la esfera del reloj estaba cubierta de polvo, y aunque se trataba de polvo seco no logré limpiarla. Nada me ayudaba a orientarme. El sol había desaparecido del cielo para reaparecer en todos los lados, quemante. El aire había quedado fijo en medio del polvo, opaco. Delante del auto quizás quince o veinte metros de polvo cobraba forma, se hacía oscuro, compacto. La presencia que comenzaba a concretarse en la nube avanzó. Detuve el auto.

–Siglos no pasaba nadie por aquí –dijo.

Fue una voz terrosa, árida. La forma, al avanzar, fue haciéndose humana. No cabía duda, era un hombre, polvoriento, pero hombre... Alejé mis vagas sospechas al mirarme y mirar a mi mujer, teníamos su mismo aspecto. Entretanto él había montado y yo continué la marcha.

–Siglos llevaba esperando –dijo al rato.

La voz me inquietó. Fue otra vez terrosa y otra vez árida y otra vez cansada y otra vez vieja, como chirrido de bisagra de una puerta cien años sin abrirse.

Miré a mi mujer, pero ella ni siquiera volvió la cabeza. Él regresó a su silencio. Las horas que siguieron me parecieron siglos. Entonces creí entender lo que el hombre había dicho. Siglos después el polvo volvió a hacerse compacto, pero en muchas direcciones. Sólo frente al auto era más claro. A los costados la nube bosquejaba estructuras, descubría formas. Formas de casuchas desvaídas, anaqueles polvorientos en polvorientas bodegas, perros trashumantes, escuela. Aquello era, o debía ser, o debía haber sido, un pueblo.

Jehanne Jean-Charles (Jean Louis Marcel Charles): Une méchante petite fille

Cet après-midi, j’ai poussé Arthur dans le bassin. Il est tombé et il s’est mis à faire glou glou avec sa bouche, mais il criait aussi et on l’a entendu. Papa et maman sont arrivés en courant. Maman pleurait parce qu’elle croyait qu’Arthur était noyé. Il ne l’était pas. Le docteur est venu. Arthur va très bien maintenant. Il a demandé du gâteau à la confiture et maman lui en a donné. Pourtant, il était sept heures, presque l’heure de se coucher quand il a réclamé ce gâteau et maman lui en a donné quand même. Arthur était très content et très fier. Tout le monde lui posait des questions. Maman lui a demandé comment il avait fait pour tomber, s’il avait glissé et Arthur a dit que oui, qu’il avait trébuché. C’est chic à lui d’avoir dit ça, mais je lui en veux quand même et je recommencerai à la première occasion.

D’ailleurs, s’il n’a pas dit que je l’avais poussé, c’est peut-être tout simplement parce qu’il sait très bien que maman a horreur des rapportages. L’autre jour, quand je lui avais serré le cou avec la corde à sauter et qu’il est allé se plaindre à maman en disant : « C’est Hélène qui m’a serré comme ça », maman lui a donné une fessée terrible et elle lui a dit : « Ne fais plus jamais un chose pareille ! » Et quand papa est rentré, elle lui a raconté et papa s’est mis lui aussi très en colère. Arthur a été privé de dessert. Alors il a compris et, cette fois, comme il n’a rien dit, on lui a donné du gâteau à la confiture : j’en ai demandé aussi à maman, trois fois, mais elle a fait semblant de ne pas m’entendre. Est-ce qu’elle se doute que c’est moi qui ai poussé Arthur?

Avant, j’étais gentille avec Arthur, parce que maman et papa me gâtaient autant que lui. Quand il avait une auto neuve, j’avais une poupée et on ne lui aurait pas donné de gâteau sans m’en donner. Mais, depuis un mois, papa et maman ont complètement changé avec moi. Il n’y en a plus que pour Arthur. On lui fait des cadeaux sans arrêt. Ca n’arrange pas son caractère. Il a toujours été un peu capricieux, mais maintenant il est odieux. Sans arrêt en train de demander ci ou ça. Et maman cède presque toujours. Vraiment, en un mois, je crois qu’ils ne l’ont grondé que le jour de la corde à sauter et ça, c’est drôle, puisque pour une fois, ce n’était pas sa faute ! Je me demande pourquoi papa et maman, qui m’aimaient tant, ont cessé tout à coup de s’intéresser à moi. On dirait que je ne suis plus leur petite fille. Quand j’embrasse maman, elle ne sourit même pas. Papa non plus. Lorsqu’ils vont se promener, je vais avec eux, mais ils continuent à ne pas s’occuper de moi. Je peux jouer près du bassin tant que je veux, ça leur est égal. Il n’y a qu’Arthur qui soit gentil de temps en temps, mais souvent il refuse de jouer avec moi. Je lui ai demandé l’autre jour pourquoi maman était devenu comme ça avec moi. Je ne voulais pas lui en parler, mais je n’ai pas pu m’en empêcher. Il m’a regardée par en dessous, avec cet air sournois qu’il prend exprès pour me faire enrager, et il m’a dit que c’était parce que maman ne voulait plus entendre parler de moi. Je lui ai dit que ce n’était pas vrai. Il m’a dit que si, qu’il avait entendu maman le dire à papa et qu’elle avait même dit : « Plus jamais, je ne veux plus jamais entendre parler d’elle! »

Poppy Z. Brite: Burn, Baby, Burn

The girl waits by the side of the road, just past Lolita age but obviously still jail-bait. She wears a pair of ragged denim cutoffs and a grubby white T-shirt bearing the logo of John Lennon's Plastic Ono Band. Her dark hair hangs stick-straight and lank to the middle of her back. July 1976, and she's pretty sure she is somewhere in New Jersey.

When a green VW bus comes along, she sticks out her thumb and watches it roll to a stop. The rear doors swing open; hands help her in. Pot smoke. Young male faces, their tufts of attempted beard and mustache like scattered weeds, barely hiding the zits. King Crimson or some other ponderous art-rock band blaring from a stereo that's probably worth way more than the van itself.

"What's your name, baby?"

"Liz."

"How old are you?"

"Seventeen," she says, adding three years. The boy looks skeptical, but Liz can tell he doesn't really care.

They offer her liquor, which she declines, and pot, which she cautiously tries because it smells so good. The end of the joint glows red as she tokes on it, so smooth, doesn't make her cough at all. She holds the twisted cigarette before her face, focusing her eyes on the small, lurid point of fire.

"Hey, babe, quit bogartin' it," says another boy. "Less a'course you want to work out a trade."

The driver swivels in his seat, making the van swerve on the road. "Gas, grass, or ass, nobody rides for free." They all laugh uproariously. Liz feels a hand on her leg, then two more encircling her wrists, not squeezing yet but letting her know they are there. Letting her know she's trapped.

They wish.

Liz hasn't hurt anyone in a long time. The images that come back to her when she does it are too unbearable. She's been learning to focus her ability, to put her power into things that don't scream and hurt and die when they burn. But she is Elizabeth Anne Sherman from the Kansas side of Kansas City, and she is still a virgin, and she's damned if she is going to lose her cherry getting raped by a bunch of stoned hippies.

Among other things, she is afraid her parents might look down from Heaven and see it happening.

So she lets the heat well up from the place deep inside her, somewhere just below the center of her chest she thinks it is, and it arrows out of her in a thin, pure ray. It's spilling from her eyes, her fingertips, and it doesn't hurt her at all, it feels good —

The ratty boys are scrambling away from her, away from the little corona of flames around her. Liz smells scorching hair, knows it isn't her own. She gathers all her strength and reins it in, sucks it in. It has taken the better part of four years, but she can control it now, and she doesn't want to kill these stupid boys.

Félix J. Palma: Margabarismos

I. Hacia

Marga

El retrete del bar La

Verónica ni siquiera merecería ese nombre. Era un cuartucho

maloliente, de una angostura de armario escobero que obligaba a orinar con la

taza incrustada entre los zapatos y el picaporte de la puerta presentido en los

ríñones, frío y solapado como una navaja. Sobre la boca desdentada que semejaba

el escusado, cuya loza exhibía barrocos churretones amarillentos, colgaba una

cisterna antigua que desaguaba en un estrépito de temporal, para quedar luego

exhausta, como vencida, antes de emprender el tarareo acuoso de la recarga.

Sobre la cabeza del usuario se columpiaba una bombilla que lo rebozaba todo de

una luz enferma, convirtiendo la labor evacuatoria en una operación triste y

atribulada. La desoladora escena quedaba aislada del resto del mundo por el

secreto de una puerta mugrienta, que lucía delante el medallón reversible de un

cartelito unisex y detrás un garrapateo de impudicias surgidas al hilo de la

deposición. Y sin embargo...

II. Con

Marga

Yo solía dilapidar las

tardes en La Verónica ,

el único bar de los que se encontraban cerca de casa que a Marga le repugnaba

lo bastante como para no ir a buscarme. Era un lugar en verdad repelente, que

parecía desmejorar día a día, como si la cochambre del retrete se fuese

apoderando lenta, pero inexorable del resto del local, de su mobiliario e

incluso de su parroquia. Cubría su suelo un mísero tafetán de huesos de

aceituna y mondas de gambas, y era difícil encontrar un trozo de pared libre de

la imaginería de la tauromaquia. Regentaba su barra un chaval granujiento que

acostumbraba a errar al tirar la cerveza, y, arrumbada en un rincón,

canturreaba ensimismada una tragaperras, hecha a la idea de seguir rumiando

sus premios durante siglos a menos que la trasladaran a algún otro negocio que

contara con una clientela menos refractaria a las componendas del azar.

En aquel escenario

nauseabundo y ruinoso me escondía yo de la implacable proximidad de mi mujer.

No es que me desagradara su compañía, pero tras el tormento de la oficina lo

que menos necesitaba era tenerla a ella rondando a mi alrededor, detallándome

las incidencias de su trabajo en el instituto, las mortíferas travesuras de los

alumnos o las ridículas cuitas sentimentales del profesorado. O, lo que era aún

peor, sentándose junto a mí en el sofá, recogiendo las piernas como una

pastorcilla y aventurando estratégicas caricias aquí y allá, buscándome las

cosquillas amorosas con la intención de restaurar la sed de antaño, de prender

en mí alguna chispa de deseo que nos condujera al lecho, o incluso a la mesa de

la cocina, sin querer resignarse Marga a la rutina emasculadora del matrimonio,

a habitar una relación que se descomponía irremediablemente con el paso de los

años, como ocurría en las mejores familias. Harto del anecdotario del instituto

y de su cruzada contra el tedio sentimental que nos envolvía, recurrí a las

migraciones vespertinas, fui probando bares y cafeterías hasta encontrar un

espacio blindado de mugre donde sus remilgos no le permitieran internarse. Nada

más lo encontré, supe que había recuperado mis tardes para emplearlas en beber

cerveza sentado en una esquina de La Verónica o, si me venía en gana, emprender

tranquilos paseos, ir al cine u ocuparme de algún otro asunto que ella no

tenía por qué conocer.

Edward Bulwer-Lytton: The Haunted and the Haunters

A friend of mine, who is a man of letters and a philosopher, said to me one day, as if between jest and earnest, "Fancy! since we last met I have discovered a haunted house in the midst of London."

"Really haunted,----and by what?----ghosts?"

"Well, I can't answer that question; all I know is this: six weeks ago my wife and I were in search of a furnished apartment. Passing a quiet street, we saw on the window of one of the houses a bill, 'Apartments, Furnished.' The situation suited us; we entered the house, liked the rooms, engaged them by the week,----and left them the third day. No power on earth could have reconciled my wife to stay longer; and I don't wonder at it."

"What did you see?"

"Excuse me; I have no desire to be ridiculed as a superstitious dreamer,----nor, on the other hand, could I ask you to accept on my affirmation what you would hold to be incredible without the evidence of your own senses. Let me only say this, it was not so much what we saw or heard (in which you might fairly suppose that we were the dupes of our own excited fancy, or the victims of imposture in others) that drove us away, as it was an indefinable terror which seized both of us whenever we passed by the door of a certain unfurnished room, in which we neither saw nor heard anything. And the strangest marvel of all was, that for once in my life I agreed with my wife, silly woman though she be,----and allowed, after the third night, that it was impossible to stay a fourth in that house. Accordingly, on the fourth morning I summoned the woman who kept the house and attended on us, and told her that the rooms did not quite suit us, and we would not stay out our week. She said dryly, 'I know why; you have stayed longer than any other lodger. Few ever stayed a second night; none before you a third. But I take it they have been very kind to you.'

"'They,----who?' I asked, affecting to smile.

"'Why, they who haunt the house, whoever they are. I don't mind them. I remember them many years ago, when I lived in this house, not as a servant; but I know they will be the death of me some day. I don't care,----I'm old, and must die soon anyhow; and then I shall be with them, and in this house still.' The woman spoke with so dreary a calmness that really it was a sort of awe that prevented my conversing with her further. I paid for my week, and too happy were my wife and I to get off so cheaply."

"You excite my curiosity," said I; "nothing I should like better than to sleep in a haunted house. Pray give me the address of the one which you left so ignominiously."

My friend gave me the address; and when we parted, I walked straight toward the house thus indicated.

It is situated on the north side of Oxford Street, in a dull but respectable thoroughfare. I found the house shut up,----no bill at the window, and no response to my knock. As I was turning away, a beer-boy, collecting pewter pots at the neighboring areas, said to me, "Do you want any one at that house, sir?"

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)