Right

now I’m eating bacon and eggs in a large restaurant in San Francisco. It’s

sunny, noisy, crowded—actually every table’s occupied, and so I’m sitting at

the bar that runs the room’s entire length, and I’m facing the long

wall-mirror, so that the restaurant behind me lies spread out before me, and

I’m free to stare at everyone with impunity, from behind my back, so to speak,

while little yelps and laughs from their chopped-up conversations rain down

around me. I notice a woman behind me—as I face her reflection—sharing

breakfast at a table with her friends, and there’s something very familiar

about her… Okay, I’ve realized, after staring at her a bit, quite without her

knowledge, that her face looks very much like the face of a friend of mine who

lives in Boston—Nan, Robert’s wife. I don’t mean it’s Nan. Nan in Boston is a

natural redhead, whereas this one’s a brunette, and somewhat younger, but

there’s so much of Nan in the way this woman moves her mouth, and something

about her fingers—her manner of gesturing with them as she speaks, as if she’s

ridding them of dust, precisely as Nan does—that I wonder if the two might be

sisters, or cousins, and the idea isn’t far-fetched, because I know Nan in

Boston actually comes from San Francisco, and she has family here.

An impulse: I think I’ll call Nan and Robert. They’re in

my phone (odd expression). I’m gonna call…

Okay. I just called Robert’s number. Immediately someone answered and Nan’s voice cried, “Randy!” “No, I’m not Randy”—and I tell her it’s me. “I have to get off the phone,” Nan says, “there’s a family emergency. It’s awful, it’s awful, because Robert…” As in a film, she breaks down sobbing after the name. I know what that means in a film. “Is Robert all right?” “No! No! He’s—” and more sobbing. “Nan, what happened? Tell me what happened.” “He had a heart attack this morning. His heart just stopped. They couldn’t save him. He’s dead!” I can’t accept this statement. I ask her why she would say such a thing. She tells me again: Robert’s dead. “I can’t talk now,” she says. “I’ve got a lot of people to call. I have to call my sister, all my family in San Francisco, because they loved him so dearly. I have to get off the line,” and she did.

I put away my phone and managed to write down that much

of the conversation in this journal, on this very page, before my hand started

shaking so badly I had to stop. I imagined Nan’s fingers shaking too, touching

the face of her own cellphone, calling her loved ones with the unbelievable

news of a sudden death. I rotated my barstool, turned away from my half-eaten

meal, and stared out over the crowd.

There’s the brown-haired woman who so resembles

redheaded Nan. She stops eating, sets down her fork, rummages in her

purse—takes out her cellphone. She places it against her ear and says hello…

—I left my breakfast unfinished and went back to the

nearby hospital, where I’d dropped a friend of mine for some tests. We called

him Link, shortened from Linkewits. For many weeks now I’d been living with

Link in his home, acting as his chauffeur and appointments clerk and often as

his nurse. Link was dying, but he didn’t like to admit it. Weak and sick, down

to skin and bones, he spent whole days describing to me his plans for the

renovation of his house, which was falling apart and full of trash. He couldn’t

manage much more than to get up once or twice a day to use the bathroom or heat

some milk and instant oatmeal in his microwave, could hardly turn the pages of

a book, lay unconscious as many as twenty hours at a stretch, but he was

charting a long future. Other days he embraced the truth, made decisions about

his property, instructed me as to his funeral, recalled his escapades, spoke of

long-departed friends, considered his regrets, pondered his odds—wondered

whether experience continues, somehow, after the heart stops. These days Link

left his house only to be driven to medical appointments in San Francisco,

Santa Rosa, Petaluma—that’s where I came in. Now, while I sat in a waiting room

and the technicians in Radiology put him under scrutiny, making sure of what

they already knew, I took out a pen and my notebook and finished jotting a

quick account of my recent trip to the restaurant and my sighting of the woman I

believed to be Nan’s sister. I’ve reproduced it verbatim in the first few

paragraphs above.

Writing. It’s easy work. The equipment isn’t expensive, and you can pursue this occupation anywhere. You make your own hours, mess around the house in your pajamas, listening to jazz recordings and sipping coffee while another day makes its escape. You don’t have to be high-functioning or even, for the most part, functioning at all. If I could drink liquor without being drunk all the time, I’d certainly drink enough to be drunk half the time, and production wouldn’t suffer. Bouts of poverty come along, anxiety, shocking debt, but nothing lasts forever. I’ve gone from rags to riches and back again, and more than once. Whatever happens to you, you put it on a page, work it into a shape, cast it in a light. It’s not much different, really, from filming a parade of clouds across the sky and calling it a movie—although it has to be admitted that the clouds can descend, take you up, carry you to all kinds of places, some of them terrible, and you don’t get back where you came from for years and years.

Some of my peers believe I’m famous. Most of my peers

have never heard of me. But it’s nice to think you have a skill, you can

produce an effect. I once entertained some children with a ghost story, and one

of them fainted.

I’ll write a story for you right now. We’ll call this

story “The Examination of my Right Knee.” It happened a long time ago, when I

was twenty or twenty-one. Since shortly after my fifteenth birthday, my right

knee had been tricky—locking into place sometimes when I bent my leg, and

staying that way until I found just the combination of position and movement

that would set the joint free again. For years I’d tried ignoring the problem,

but it had only gotten worse, and so, during my junior year as an

undergraduate, I reported it to the experts at the university hospital. An

X-ray indicated torn cartilage. The head of Orthopedics himself was going to

take a closer look, and I waited in a hallway outside his door in a green robe

and paper slippers.

Almost nothing went on in this hallway. Now and then a

medical person in green or white padded by. After a while, about fifty feet

along the corridor, a middle-aged man in a dark business suit started talking into

a wall-mounted payphone. For most of the conversation his back was turned to

me, but at one point he pivoted with a certain frustrated energy, and a few of

his words reached my ears: “I was never an animal lover.”

At that moment the door I was waiting for opened, and an

orderly in white asked me to come in.

I followed this orderly not into a tiny examination

room, but instead onto a brightly lit stage in an auditorium filled with

hundreds of people—medical students, as best I could make out against the glare

illuminating me. Nobody had warned me I’d be exhibited. In the center of the

stage, under blinding lamps of the kind portrait photographers use, the orderly

helped me onto a gurney and posed me on my back like a calendar girl, the knee

raised, the robe parted, my bare leg displayed.

In those days I took recreational drugs at every

opportunity, and about an hour earlier, as a way of preparing for this

experience, or maybe just by coincidence, I’d ingested a lot of LSD, which had

the effect of focusing my awareness more acutely on the pain in the knee, at the

same time unmasking pain, in itself, as something cosmically funny, as well as

revealing the overwhelming, eternal vitality of the universe, especially of the

dark, surrounding audience, who breathed and sighed in unison, like one huge

creature.

The head of Orthopedics approached me. He was either a

large, almost gigantic person, or a person who only seemed gigantic under the

circumstances. He gripped my flesh with his seething monster- hands and

delivered a lecture while he manipulated my lower leg and fondled the joint in

preparation, I felt pretty sure, of eating me. “Now you’ll see how the

disfigured cartilage causes the joint to seize,” he said, but he couldn’t

produce the effect, and went on straightening and bending the leg at the knee

and talking jibber-jabber. Meanwhile, I observed that the Great Void of

Extinction was swallowing the whole of reality at an impossible rate of speed,

and yet nothing could overcome our continual birthing into the present.

The Colossus of Orthopedics clamped my thigh with one

hand and my ankle with the other and cranked the lower leg around gently, then

not so gently, saying, “Sometimes it takes a bit of fiddling.” Still the knee

didn’t lock. Before this vast audience of his students, he pronounced me a

faker. “There’s no condition here requiring any treatment at all,” he said. He

pointed at me with a finger that

communicated

billions of accusations simultaneously. “A lot of these young men are out to

fool the medical establishment, because they don’t want to get drafted.”

It was easy enough for me to get the knee to lock. I

just had to bend my leg so the knee was raised and turn my foot forty-five

degrees to the right. The noise it made when it locked was disgusting—a horrid,

gulping thunk. The sound came from the pre-chaotic depths, where good and evil

were one thing.

“Ah—you see,”—the mammoth said to his compatriot, the

darkness. “Now you see!” I understood this to mean he was about to turn me

invisible, and soon after that he’d amuse the students by making me explode.

Then I grasped that he was an orthopedic specialist who, having failed to get

the knee locked until I’d done it for him, was now going to show his students

how to unlock it again. But he couldn’t do that either. After a lot of huffing

and puffing and mumbo jumbo, he collapsed in his inwardmost self and prayed

unto the darkness for help, and his prayer was

heard.

The darkness furnished forth the Unlocker, who seemed a

loving emanation, then a mysterious becoming, then a glorious actuality, and at

last a sort of porky med student, who leapt onto my knee hind-end- first, as

you’d do if you wanted to shut a bulging suitcase. Again the great sound, the

Gulp of God, and my bones were restored, and with an infinitude of applause too

wonderful for human ears, Creation burst its beginnings. The hero took my hand,

and, having been exhibited before the All, having been lain out, and locked,

and unlocked, at his touch I was able to rise, and walk.

In the quiet hallway I sat down alone. The man who’d

been talking on the payphone was still there, still talking, as if nothing had

ever happened. I strained to hear his magical words. For what it’s worth, I’ll

repeat them here. He said: “Your dog. Your dog. Your dog. You were a fool to

leave your dog with me.”

You’re writing about one thing, next second about

something else— things medical—things literary—things ghostly—and onto the

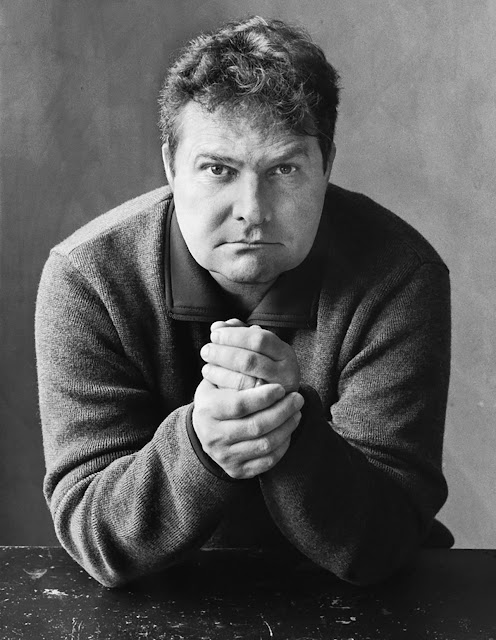

empty page steps a novelist named Darcy Miller. Among other books, Darcy wrote

one called Ever the Wrong Man, which

became a movie in 1982

—Darcy

also wrote the screenplay. He published as D. Hale Miller. Incidentally, I’m

aware it’s the convention in these semi- autobiographical tales—these

pseudo-fictional memoirs—to disguise people’s names, but I haven’t done

that…Has thinking of Link, my sick friend, brought Darcy to mind? The two men

were quite similar, each ending up alone in his sixties, resigned and

self-sufficient, each one living, so to speak, as his own widow. And then the

ebbing of self- sufficiency, the gradual decline—gradual in Link’s case, and in

Darcy’s quite a bit swifter.

I made Darcy’s acquaintance in the year 2000 in Austin,

Texas, where he lived in an old house on an abandoned ranch. That sounds

glummer than it was. Darcy had come there for a four-month period at the invitation

of the University of Texas, which owned the ranch and maintained the premises,

and he got a stipend, probably a meager one, but anyway he had a roof over his

head, and he wasn’t broke. I happened to be teaching a writing course at the

university that same semester, and one day in early spring I led my dozen

graduate students, in three cars, out to the old place to hold our class there

as Darcy’s guests. We headed west out of Austin, first onto backcountry roads

and then off the paved byways entirely, crossing two large ranches on a

miles-long dirt easement and meeting a series of widely separated gates we had

to unlock and open (I’d been given the combinations on a slip of paper) and

shut and lock behind us. By the odometer we traveled three dozen miles, no

more, and on the map we moved well short of one-half degree westward in

longitude, but Austin is situated such that this brief journey took us out of

the lush southeastern part of Texas and into the scrubby semidesert of the

state’s southwestern half, where you need ten acres of this mean, miserly

grass, an old cowboy once told me, to keep one head of cattle from starving;

fording with a splash and gurgle a tiny creek within sight of the house and the

stables behind it, passing under creekside cottonwoods and shaggy willows,

planted long ago for windbreaks and now grown monumentally large, and swinging

around Darcy’s car, a well used fake-luxury Chrysler parked just across the

creek and still some distance from the house,

as if it had made it very nearly the

whole way and

then given up.

Darcy seemed like that too, a little. He had tousled

reddish hair and puffy features and looked something like a child snatched from

a nap. He had ice-blue, very shiny, bloodshot eyes, and on his cheeks and across

his nose the burst capillaries once known as “gin blossoms.” We gathered behind

the house on a patio of broken flagstones—the interior was a bit too small for

entertaining. Darcy served us iced tea poured from two large pitchers into old

canning jars, and that’s what he drank, too, as he described for us the stages,

a better word is paroxysms, by which his first novel had become a successful

movie more than a decade after its publication. First the producers added years

to the hero’s age and signed John Wayne; some weeks into the development

process, however, John Wayne died. They dialed back the hero’s age and cast Rip

Torn, Darcy told our class as we sat around a crude wooden table in the

willows’ shade, but Rip Torn got arrested, not for the first time, or the last,

and then an actor named Curt Wellson turned up, absolutely perfect for the

role, the success of the project so assured by this young man’s unprecedented

talent that he held out for an unprecedented fee for his services, lost his

chance, and was never heard of again. Clint Eastwood liked it, and said so for nearly two years before negotiations

hit a wall. In a fit of silliness, pure folly, the producers took an offer to

Paul Newman. Newman accepted. The film was shot, cut, and distributed, and it

did all right for everybody involved.

Nothing much had happened since then to D. Hale Miller,

at least not in the eyes of my students, that was plain, although for better

than thirty years he’d survived, and occasionally thrived, as a writer—of

unproduced scripts, uncollected magazine articles, and two more novels after Ever the Wrong Man. All three books had

gone out of print.

Throughout our visit Darcy seemed in good spirits and in

command of himself. He dealt generously with the works under discussion, though

he addressed the students—men and women in their mid- twenties—as “you

children.” He wore baggy Wrangler jeans, a light checked short-sleeved shirt,

and flip-flop zoris, their yellow straps

gripping

mythically horrible feet—knobby, veiny, with toenails like talons. I shouldn’t

have been staring at them, but shortly into the visit I found I didn’t like my

students’ attitude and wished we hadn’t come here, and I focused on such

irrelevant details as Darcy’s feet in order to cancel out the rest, the

physical vastness of empty Texas, the heartfelt, demoralized lowing of distant

cattle, the buzzards hanging in the sky, all of that, and in particular the

young writers around the table, attentive, encouraging, yet thoroughly

dismissive. They could see Darcy’s exile but not his battered nobility. The

waves had rolled him half-alive onto foreign sands, and now he was sipping his

tea, commenting on our attempted stories, and slowly shifting the position of

his left elbow to dislodge a fly that kept landing on it. I’m not sure how the

day ended and I don’t remember the trip back into Austin, but I recall stopping

at a video rental shop later that night, or on a night soon after, looking for

a copy of Ever the Wrong Man. The

store’s catalog listed the title, but it was missing from the shelves.

That was my first encounter with Darcy Miller. The next

one came five or six weeks later, after I got a completely unexpected message

at work: I’d received a phone call from the writer Gerald Sizemore, G. H. Sizemore

on his books and Jerry to his acquaintances. As soon as I got his message I

called him back, and after a quick hello he went right to the point: “I want

you to go out and see Darcy Miller. I’m worried about him.”

I’d never met Gerald Sizemore, and we’d never even

corresponded, but it didn’t surprise me that I was known to him and that he

felt, moreover, that he could ask of me just about any favor, because some

years earlier I’d written an introduction for the twentieth anniversary edition

of his first novel, The Reason I’m Lost, published

in 1972 and now, as I’d argued in my preface for it, an American classic. Like

Darcy Miller, Sizemore had published three books but had lived mainly as a

screenwriter, with fair success; had written many scripts, including one he

co-authored in the early 1970s with, as he told me now, Darcy Miller: a

romantic romp starring Peter Fonda and Shelley Duvall that had been filmed in

its entirety but never actually finished—a union strike interfered with post-production; the studio changed

hands and

the

new owners filed for Chapter Eleven; in the middle of it all the chief

cinematographer ran away to Mexico with the director’s wife; and so on—and

therefore never distributed. I’d been completely unaware of Gerald Sizemore’s

connection with Darcy Miller. Jerry, as he invited me to call him, described

his and Darcy’s alliance as reaching back into their twenties, and the plot,

such as it was, of The Reason I’m Lost paralleled

the course of their friendship as young writers learning their craft in the San

Francisco scene of the early 1960s. Later, in the 1970s, after the hungry

years, Darcy and Jerry shared their successes together—books coming out, a

movie being made, money coming in. That was back when writers were still sort

of important and, as with athletes, “promise” draped even the unproven ones

with a certain glamor. I’ll offer myself as an example: I was, in those days,

eighteen and nineteen and twenty years old, and newspapers in Chicago and Des

Moines ran articles about me because I was someday going to be a writer—I

wasn’t one yet, I was just going to be, and on the strength of this expectation

I was invited to ladies’ clubs throughout the Midwest to read from the couple

of dozen existing pages of my work and answer questions from club members, and

there were two or three of these mid-western, middle-aged, formerly

good-looking women I could probably have seduced (though I lacked magnetism and

still had acne) because in 1972 it would have been an adventure to be seduced

by a figure of future literary prominence, and later watch him rise. Meanwhile,

Darcy and Jerry were having the time of their lives as figures of current

literary prominence, adventuring with currently good-looking women, mostly in

Darcy’s big home by the Pacific in Humboldt County, California. That would have

been around the moment of my fame as a medical curiosity at the University

Hospital—I told you about that—which is maybe why that old college memory

surfaced a bit ago, and there’s the fresher memory, too, of my recent

experience taking care of my close friend Link; and those two memories together

led me to recollect Darcy and…but we’ve already mentioned the conjoining of

these memories, so what’s the fuss? I’ll get on with it. Jerry was worried

about his old friend. “I don’t know what’s going on out there,” he said, “at

that ranch, or farm, or—”

“The Campesino Place.” “So it’s a place?”

“In Texas, a ranch would be thousands of acres. A couple

hundred is just a place.”

“Darcy doesn’t answer his phone, and his message machine

is full— anyway it drills your ear with this endless, screaming beep, and then

it hangs up, and I assume that means it’s full—and for more than a week now I

can’t get a rise out of the guy. The lady at the Writing Center— Mrs.—”

“Mrs. Exroy—”

“Mrs. Exroy. Interesting name. She says you saw Darcy a

couple months ago. Did he seem all right?”

“He seemed fine

to me. I mean, he’s how old—?”

“He’s sixty-seven. The thing is, before he stopped

answering the phone, he called me several days in a row to bitch and complain

about his brother. Says his brother and his sister-in-law turned up last month,

and he can’t make them leave. They’re messing up the kitchen, drinking his

liquor, getting in his way.”

“So maybe it’s not such a concern, then, if

he’s got family there—” “No. I’m very concerned.”

“But if his brother’s there—”

“His brother’s been dead for ten years.”

This was the kind of moment when, in the distant past,

I’d put a cigarette between my lips and light up and take a drag—but I don’t

smoke now—in order not to seem stupefied.

“They’re both deceased. The sister-in-law

died more recently.” I said, “Ah-hah.”

“She died in ’95. I went to both their funerals.” I said again ah-hah.

“So Darcy Miller’s

hanging around with a couple of ghosts,” Jerry said, “or claims to be.”

I promised him I’d get out there and have a look.

As soon as we’d said goodbye, I tried Darcy’s number

without even putting down the receiver. Following several ring tones came a

long, long beep, and the connection ended. Only then did I place the receiver

in its cradle on my desk. I was in my office at the Writers’ Center, which

looked down, on the window side, at the four lanes of Keaton Street and,

through the doorway on my left, at the grandly proportioned mesquite table

around which we gathered our seminars. The conference room itself was a modest

space lined with shelves of books, once the study of the Texas author Benjamin

Franklin Brewer and still containing the old pale green—springtime

green—leather reclining chair in which Brewer sat and read, and made his notes,

and, one day, stretched out and died. The building had formerly been Brewer’s

home. At the moment, around four on a Friday afternoon, I had the upper floor

to myself—three offices, a bathroom (with tub)

and the conference room. Sometimes, when alone up here like this and

trapped in a melancholy mood, I sat in the recliner and operated its antique

mechanism and lay back and tried to imagine the going out of Benjamin Franklin

Brewer’s last breath. Under the influence of these surroundings, I thought I’d

better go right now and look in on Darcy Miller.

Downstairs I got the combinations for the gate locks

from the center’s administrative assistant—this was Mrs. Exroy, a plump,

diligently pleasant older southern widow who liked to stand on the back porch

and smoke cigarettes while gazing at the little ravine and the creek out back

of the building, as if the trickle of water carried her thoughts away. She

always brought to my mind the phrase “sweet sorrow.”

I got on the road not long after 4 p.m. Right away the

traffic ensnarled me, if that’s a word, and it was well past five by the time I

came to the dirt roads. It seemed to me I’d reach Darcy’s home with plenty of

daylight left, but I wasn’t sure of any daylight coming back; to save troubling

with the combinations later in the dark I left the gate locks open and

dangling, a scandalous breach of cowboy etiquette, but one I expected to go

unnoticed because from horizon to horizon, as I realized now, making the trip this time without

passengers to divert

me,

not a single shelter was visible, and I saw nothing, really, other than the

gates and the miles of smooth wire fencing, to suggest that anybody cared what

went on here or even knew of the existence of this place. I passed a few

longhorn steers, or bulls, or cows, I couldn’t have said which, a very few,

each standing all alone beneath the burden of a pair of horns that reach, from

tip to tip, “up to seven feet,” according to absolutely every article I’ve ever

seen about these animals; they wear out the phrase. Here in the Americas we

trace the longhorn line back to the livestock cargo of Columbus’s second

expedition to the New World, and farther back, of course, in the Old World, to

a scattered population of eighty or so wild aurochs domesticated in the Middle

East more than ten thousand years ago, the forebears of all the cattle living

now under human dominion. In 1917 the University of Texas adopted as its mascot

a longhorn steer named “Bevo.” As far as I’ve been able to determine, the two syllables

mean nothing and may derive from the word “beef.” In 2004, a successor

Bevo—Bevo the Fourteenth—attended George W. Bush’s presidential inauguration in

Washington, D.C.

At the fourth gate, the final one, I knelt before the

lock while my Subaru idled behind me. Way up the straight road I could make out

the willows and cottonwoods surrounding Darcy’s house, and looking at my

destination and the half mile of empty ground between us, I was overwhelmed by

a clear, complete appreciation of the physical distance behind me, as if I’d

walked the twenty-some-odd miles rather than driven across the landscape in a

car. A few minutes later, when I came in sight of the creek, I witnessed a

school of vultures, the huge redheaded scavengers called in these parts turkey

buzzards, nine or ten of them, eleven, I couldn’t count, orbiting above the

house on spiral currents. I stopped

my car and watched. The truth is I was afraid

to go any farther—no word from the house’s occupant for many days, and now

these circling creatures, taken everywhere as omens of death because they

forage by smell, scouting the thermal drafts that carry them for any whiff of

ethyl mercaptan, the first in the series of compounds propagated by carnal

putrefaction and one recognizable to many of us, I’ve since learned, as the agent added to natural gas in

order

to make it stink. Floating above the house, the buzzards looked no more

substantial than burning pages, gliding very gradually downward but then, after

no perceptible alteration or adjustment, gliding upward, mounting high enough

to seem no longer invested in the scene below, wherein none of the

things—Darcy’s car, the house, the row of six whitewashed stables roofed with

black asphalt shingles

—seemed out of the ordinary, but neither did anything seem to move.

Suddenly I felt as if the view before me had shrunk to the size of a tabletop.

To the east, hundreds of meters beyond the buildings, the buzzards’ shadows

raced over the scrubby tangles of a mesquite chaparral like the shadows of a

mobile in a child’s bedroom. I engaged the accelerator and moved

forward—shrinking now, myself, in order to enter among the miniatures and the

toys.

As I banged on the house’s door, the buzzards twenty and

thirty feet above me showed no reaction and continued their rondelle. I heard

nothing from inside, peeked in the living room window—saw nobody— banged some

more—still nothing—and was reaching out my hand to test the knob when the door

came open and Darcy Miller stood before me. He wore a striped lab coat, and he

was barefoot, if I recall, although it’s hard to recall, because the lab coat

was hanging open, and beneath it Darcy seemed to be completely naked, and I

didn’t know where to look. So I didn’t look

anywhere.

Darcy made no greeting, only studied me until I

re-introduced myself and asked him if he was doing okay. He said, “Perfectly

okay.”

“Jerry Sizemore asked me to come out because he can’t

get you on the phone. What have you been doing with yourself out here?”

“Thangdoodlin’.” “Thangdoodlin’?”

He turned away and sat down on the couch without

explaining the term—also, I’m afraid, without closing his robe—and I sat down

beside him. I feel a natural impulse here, having just entered Darcy’s personal

field, to stop and describe his face—the bloodshot, ice-blue eyes, the fishnet

grapestains over his nose and cheeks—or his horny feet, or his crop of wispy

hair once probably reddish, now translucent—but, as I say, I was blinded by my

embarrassment, and I can now offer only the

additional

details that Darcy smelled like booze and that I heard the faint whistle of

breath in his nose just the way I heard the breathing of grownups through their

hairy, cavernous nostrils when I was a child. For a little bit, that was the

only sound in the house, the whistling of Darcy’s nose…He said, “I think I can

make you some tea. Is that what you want?”

“First,” I said,

“can we talk a little about what’s going on with you?

Jerry’s worried, I’m worried—” “What’s got you so

worried?”

I felt lost. “Well, I mean, for one thing, you’ve got

your robe open there, and your package is just—hanging out.”

The lab coat closed with metal snaps. He fumbled with a

couple to get it shut. “Maybe I’m expecting a young lady.”

(Now I noticed faint freckles on the backs of his hands

and noted how pale were the little hairs. His lips were gray and blue, as if he

were cold.)

“Jerry thinks you might be losing it out

here.” “Losing what?”

“Your mind.”

“Who wouldn’t? Let’s have a cup.”

He led me into a short passageway with the linoleum-era

kitchen on the left, the door to a “spare room” across from it on the right,

and the master bedroom and bath at the end. We sat at the wobbly Formica table

in the kitchen while Darcy, with a fastidiousness arising, I would guess, from

a sense his competence was under review, got out all the stuff and brewed us a

pot of Lipton’s tea. I went right to the subject of the visitors—the ghosts—and

he said, “No, they’re not ghosts. It’s them. They’re alive.”

“Even though they’re both dead and

buried.” “Yeah.”

“But Darcy,

don’t you think that’s—crazy?”

“Certainly! It’s the craziest thing ever. Yesterday I

saw Ovid walking out there by the stables,” Darcy said, much to my confusion,

until I

realized Ovid must be the brother, “and we

sat over there on that big old cottonwood stump, side by side, and talked.”

“Can I ask what you were talking about?”

“Nothing too specific. Just this and that.”

“Did you ask Ovid to

explain his presence? Did you remind him he’s supposed to be dead?”

“No! What would you think

if I said to you right now—Hey, man, you’re supposed to be dead?”

“I don’t know.”

“How would that fit into any reasonable or

polite conversation?” “I don’t know.”

“Neither do I.”

“Darcy, when was the last time you had a

checkup?” “Oh. Hell. A checkup?”

“Do you have a doctor here in Austin?” “No.

But I have a nurse in San Francisco.”

“You have a nurse? What does that mean, you have a nurse?”

“She’s more of a girlfriend. But she’s a nurse at Cal

Pacific. She’s a Native American. She’s Pomo Indian.”

“Do you two talk

on the phone?”

“Sure. She’s very tuned in to this sort of business, the

ethereal waves and the currents, or anyway she says she is—the spirits and the

haunts and the songs of the mother Earth.”

“So, then, you’ve told her about all this—about your

dead brother and dead sister-in-law visiting you?”

“Yeah.”

“And what does she say?” “She says it means

I’m dying.”

Well, I could see that as one possibility. But not as a

result of illness, only as the inevitable outworking of the days of D. Hale

Miller, and it was a lot like the destiny I’d pictured for myself when I was a

criminally silly youth: a washed-up writer with books and movies and

affairs

and divorces behind him and nothing to show for it now, eking out a few last

years—drinking, sinking. Of course in my youth it had seemed romantic because

it was just a picture. It didn’t have an odor. It didn’t smell like urine and

alcoholic vomit. And the way I’d been rushing at it, if I’d continued toward

that kind of end it would have come a lot sooner, in my twenties, if I had to

guess, preceded by not much.

“It doesn’t look like your car has moved.” “It works fine, but I

don’t like to drive it.” “How do

you get supplies?”

“They bring

stuff. Bess and Ovid. They bring everything.”

We drank our tea, which wasn’t bad. Darcy had puffy red

hands, the flesh extremely wrinkled, and as I studied his fingers they began to

look like eight dancer’s legs clothed in droopy stockings of flesh, marching

and kicking around the tabletop in front of him, pushing his china cup and

saucer around, leaping onto and wrestling with a crisp clean orange-and-white

University of Texas baseball cap, which he never placed on his head. My plunge

into despair felt vividly physical. If I’d closed my eyes I’d have been sure a

colossal savage was dragging my chair through the floor and down through mile

after mile of the dirt below. If I’d had control of my senses, my awareness,

which I did not, I’d have noticed the afternoon had turned toward evening, and

I’d have looked around for a light switch. We sat in a deepening gloom.

“Darcy, these

visitors, Bess and Ovid—where are they right

now?”

One of his fingers fluttered upward from the table,

dragging the rest of the hand with it, to point across the hallway. He said,

“Look”—and I looked, terrified my gaze might follow this indication right into

the faces of two ghosts, but he concluded—“in that room.” He meant the spare

room.

I stood up and entered the hallway. I won’t pretend I

had any thoughts at all, only sensations, a coppery taste in my mouth, a

pervading weakness, mostly in the legs, a buzzing around my temples and behind

my eyes. I put my hand on the door’s old-fashioned tongue latch, but for

several seconds I couldn’t operate my own fingers. I

remembered

this spare room from my first visit to the U of Texas a few years earlier, long

before Darcy ever came there. The room lay in the center of the house and may

originally have been some sort of pantry, I

don’t know. It lacked windows and amounted to a twelve-by-twelve- foot box

constructed of yellowing whitewashed planks. Over the years the seams between

the planks had opened to finger-wide gaps which had been stopped with

spray-foam insulation that congealed in grotesque, snotty rivulets reminiscent

of limestone cave formations, hard to look at but impermeable to scorpions.

Mrs. Exroy, who’d given me the tour, had told me about the scorpions and said

the foam insulation was there to keep them out—that is, to imprison them in the

darkness behind the walls—while an image of them poured through the cracks into

the impressionable mind, teeming there with their stinger-tipped venom sacs

waving at the ends of their segmented tails and their pincers clacking like

castanets on the ends of their loathsome pedipalps. I now felt convinced that

something real, something horrid was happening to this man in this house, and

the bizarre shrinking sensation I’d experienced earlier was now explained

(despite remaining utterly mysterious) as the result of my having passed

through a succession of ever smaller perimeters whose entries I’d breached as

if in my sleep, blind to their significance—each of the four gates; then the

creek; then the constellation of the vultures at this moment still wheeling

above the roof; and finally the bounds of the house itself—toward the pair of

entities, Bess and Ovid, waiting behind this

door.

I depressed the latch and pushed the door wide, and the

twilight from the hallway fell across the only things in the space, a

single-size metal bedframe and its bare, grayed, filthy mattress—only these two

objects, twisted invisibly by the several concentric gales of power whirling around

them for a radius of twenty miles. A bit of light touched the walls, enough to

reveal that they were undisturbed, and still disturbing. The disfiguring goop

had the sandy pallor and plasticine shine of a scorpion’s exoskeleton, so that

to me it appeared multiple tons of scorpions were being mashed against the

wall’s other side and extruding from the cracks. I shut the door fast, like a

frightened child.

To be clear, I hadn’t

seen any scorpions or any people or any ghosts. I joined Darcy in the kitchen.

Fear had eaten up my patience. Sitting down I was rough with my chair.

“Somebody’s bullshitting somebody.”

“Maybe they’re on a walk.”

“Where did these visitors come from in the first place? The underworld?”

“Oklahoma.”

“How’d they get here, Darcy? Where’s their

car?” “I don’t know. In one of the stables, maybe.”

“I can look right out this window and tell

you the stables are empty.” “Or maybe they’re on a drive.”

“When was the last time you saw these two

people?” “I don’t know—an hour ago?”

I think the change in my manner sobered Darcy. He became

instantly cooperative and peered into my face and nodded his head as we agreed

that come Monday I’d make calls and get him the soonest possible date with a

doctor. More disturbing than the idea he was trafficking with hallucinations

was his blank-faced toleration of the circumstance. This weird placidity seemed

to be his chief symptom— that, and failing to shut his robe—but symptomizing

what?

Before saying goodbye I went through the house and

turned on all the lights, leaving the spare room closed and dark. For this

operation I got Darcy’s permission first, naturally, and a bright interior

seemed to cheer him up. When we shook hands on parting, he gripped mine firmly

and cracked it like a whip.

I drove from gate to gate across the pastureland with

the sunset on my left. Along the way I passed a scene of carnage: half a dozen

redheaded vultures on the ground, beleaguering a carcass too small to be seen

in their midst. When we catch sight of one of these birds balanced and steering

on the currents, its five-pound body effortlessly carried by the six-foot span

of its wings and therefore not quite constituting a material fact, the

earthbound soul forgets itself and

follows

after, suddenly airborne, but when they’re down here with the rest of us,

desecrating a corpse, brandishing their wings like the overlong arms of

chimpanzees, bouncing on the dead thing, tearing at it, their nude red heads

looking imbecilically minuscule and also, to a degree, obscene—isn’t it sad? By

the way, the ones circling above the house were gone by the time I left the

place, and no explanation for them has ever suggested itself. I’d left after

only an hour’s visit, and had an hour of daylight before the evening overtook

me on the freeway into Austin and bathed the city in a purple dusk in which the

lights floated and we assume everyone is happy.

That year, the year 2000, our small family—mom and dad,

son and daughter, dog and cat—had wintered comfortably in Austin, and now the

others had flown north to our home in Idaho and left me, during Finals Week, on

my own and accountable to nobody for my evenings. After that baffling afternoon

at Darcy’s I drove back to the Writers’ Center, where I could park, and walked

through the muggy southern evening to the arid oasis of the University’s

undergraduate library. At a table in an alcove on the third floor I opened a

blue-bound, musty copy of The Reason I’m Lost and read about Gabe

Smith and Danny Osgood, two San Francisco jazz men who live far from the

recording studios and deep in the sorrow and glory of artistic struggle.

I turned first to a five-page passage late in the

book—an argument between Osgood and his girlfriend Maureen, the first bit of

dialogue I’d ever scrutinized for its ups and downs, the turns and turns-about,

the strategies of the combatants. These long years later I could still recite

the lines along with the characters, yet they sounded new.

I looked back at the novel’s opening paragraph, and by

midnight I’d read the whole thing again and found myself just as moved as I’d

been the first time—the first dozen times—every time. The Reason I’m Lost wasn’t just an exercise in exemplary prose.

Ultimately this book, and my envy of it, were about the friendship between

Danny Osgood and Gabriel Smith. A private and a corporal, they meet as members

of the Sixth Army Band at the Presidio military fort in San Francisco, spending

time, often while AWOL, in such jazz clubs as the Black Hawk in the Tenderloin

and Bop City in the Fillmore

district (both

clubs

really existed), and graduating into a civilian life fraught with glamor and

ugliness and every kind of love—thwarted love, and crazy love, and victorious

love—above all, the love between these two friends.

Darcy was on the University’s insurance plan, and after

a journey through a delicate labyrinth of abysses, of blind corners and dead

ends, switcheroos and doublecrosses, but with Mrs. Exroy to guide me step by

step through the dark, we’d landed Darcy Miller an appointment at the South

Austin Medical Associates on Friday, a week following my visit with him. In the

meantime, Jerry Sizemore made arrangements to come down for a probably lengthy

stay. My former melodramatic mood, the morbid fear and the helpless pity, had

given way to a strange giddiness. The truth is that I wondered if out of all

this might come three friends—I might be added—I know it’s stupid— am I the

only grown man who still longs to be friends with other boys?

In the book the two friends Gabriel and Danny refer to

each other as “Gee” and “Dee.” I noticed that Jerry and Darcy had the same

habit— this over the telephone during the course of that week, one conversation

with Darcy, and several with Jerry, who called me nightly delivering the good

news that again today Darcy had been reachable and happy to chat as he looked

forward to meeting his new physician.

The morning of the doctor’s appointment I called Darcy

three times and got no answer. Each time I left a brief reminder of the

appointment along with the assurance I’d be turning up there by 10

a.m. Each time the beep got longer, and each time, as I hung up, the

thud in my belly felt a tiny bit more dreadful.

Taking the ranch roads a little too fast I kicked up a

storm of dust that pursued me across the plains and overran me when I stopped

to unlock and relock each of the gates. I saw no buzzards floating above the

Campesino Place, only random cumulus formations that made the morning sky look

like a large, comfortable bed. As I eased my vehicle over the creek, I noted

that Darcy’s Chrysler seemed to have settled more exactly into its place a bit

too far from the house, its burgundy hood and convertible top drifted with

white seed-fluff from the female cottonwoods.

I knocked on the door while working the knob. It wasn’t

locked, so I opened it, and although I believed I’d heard a faint shout from

somewhere inside, I entered a large, unfilled silence.

“Darcy,” I called, “Darcy—are you

here?” “Yeah!” came from the rear of the house.

I followed the sound down the hall past the kitchen and

toward the bedroom at the back, which was the master, more or less—the only

genuine bedroom—and just inside this bedroom’s door lay Darcy Miller on the

wooden floor, flat on his back with his head in the hallway, staring out of his

watery blue eyes in what I read, upside- down, as bitterness. A mess of dried

blood covered the floor around his head like a corona, but he didn’t seem to be

bleeding now. I knelt beside him and could think only of swear words to say, so

I said them, and Darcy said, “You got that right.”

After a quick run-through of everything I possessed in

the way of remedies and responses, after checking for a pulse and finding none—

although Darcy’s chest rose and fell and I could hear the breath in his

throat—after establishing that he could tell me the date and his name and

asking him to take each of my hands and give a squeeze, which he managed all

right with equal strength in the right and the left, I abandoned him and called

911 from the phone in the living room. While the emergency dispatcher and I

very carefully went over the digits of each gate combination, I noticed that

the living room lamp, the overhead light, the one in the hallway—all the lights

in the house— were burning, just as I’d left them seven days previous.

With a reluctance I identify, now, as shameful, I

returned to Darcy where he lay on the floor still conscious and still peering

straight upward. He wore gray sweatpants and one slipper, the other foot bare,

and he wore no shirt, though he’d pulled his lab coat and covers from the bed

down onto himself and got some protection from those. I recalled an exchange

from The Reason I’m Lost between Gabe

Smith and Danny Osgood—and here, stretched out on the floor with his eyes

moving back and forth, poring over the ceiling as if it were a problem in math,

was the real, the original, Danny Osgood—this exchange:

Gabe: “How old

is that old guy?”

Danny:

“Something short of dead.”

I went from kitchen to hallway with bath towels and dish

towels and a quart pan spilling tap water, cursing out loud, I’m sure, the

whole time, and bringing no real comfort to the old guy on the floor. My heart

ached, I tell you, and it’s likely I shed some tears, but within half an hour I

felt convinced Darcy wouldn’t die, and I was going back and forth from the

living room window to the hallway, reporting to him on the somewhat comical

progress of an ambulance careering toward us over the prairie with its

red-white-and-blue lights revolving and the we-you,

we-you of its siren rising and vanishing in the empty morning and finally

cut short with a yip as the van lurched over the creek (not quite sideswiping

my Subaru) and a generation of medically trained people hatched out of it and

cartwheeled into the house—only four such people, it turned out, but with their

equipment, and the scene they created, the ministrations and communications,

the gurney and the portable defibrillator and ventilation pump and the blood

pressure devices, the fixing of electrodes and the clearing of airways and the

search for a useable vein, all accompanied by syncopated cries and whispers,

the loud voice of the man on the walkie-talkie and the lower tones of the man

and woman establishing intravenous hydration and fitting the oxygen mask, which

descended like a judgment to cover Darcy’s liverish mouth, and the silent

fretting of the fourth technician, a petite baldheaded man, who did nothing, I

have to say, but move from one to the other of his cohort, looking over

shoulders—they multiplied and magnified themselves. Meanwhile, I used Darcy’s

phone to call Jerry Sizemore, and by the time I’d filled him in, the ambulance

had fled across the creek again toward the ranch road, spinning water from its

tires, leaving me alone in the kind of silence following a slap in the face.

I reached the hospital within forty-five minutes—a time

nearly doubled while I searched for a parking space—and the ER’s doors parted

before me with a groan and a sigh and then a thump, and I entered the waiting

area. At this moment I had no thought for anyone but Darcy—I was concerned that

we were separated, and that without an advocate he’d end up sidelined in a

hallway or even a storeroom or

a

loading dock; I wanted to find Darcy and had no time for comparing this

experience with any other—but now, in my pajamas, with the coffee, looking

back, I see that the Parkland Community Hospital’s emergency room doors opened

onto a new phase of my own life, one I can expect to continue until all

expectations cease, the phase in which these visits to emergency rooms and

clinics increased in frequency and by now have become commonplace: trips with

my mother, my father, later my friend Joe, then of course with my friend

Link—and eventually me too—the tests, forms, interviews, exams, the journeys

into the machines. By the time I reached the hospital, Darcy had been taken

well in hand and begun going through all of these things, and probably more.

I’d expected to wait in the anteroom among the sick and wounded and their loved

ones bent over mystifying paperwork or staring down at their hands, beaten at

last not by life but by the refusal of their dramas to end in anything but this

meaningless procedural quicksand…No, between his visits to the technicians, the

staff let me wait with Darcy in the realm behind the veil, in the Trauma

Theater, a vast area cut up by moveable white partitions screening my view of

the surrounding moaners and weepers and their powerless comforters. Whom I

obviously heard.

From time to time as the morning turned to afternoon

they wheeled Darcy away on his gurney, leaving me to sit in a three-walled cell

in a collapsible chair that was now its only piece of furniture, among all the

equipment from which Darcy had been disconnected before his disappearance into

the rest of his adventure.

After he was taken away several times and brought back

each time, they left us together for a long interval. The 3-to-11-p.m. shift

came on and the sun crossed the parking lot and it got half dark outside. Darcy

wanted something cold on his tongue. I fed him some pink ice cream from a cup

because he didn’t seem able to control his fingers. Nobody came. On the back of

Darcy’s head a patch of scalp had been shaved bald and a square inch of white

bandage planted in the middle of it. Every so often—every three or four

minutes—he pointed at his head and said, “They gave me a couple stitches.” He

made errant remarks— they weren’t remarks about anything around here. “Nice day

with the

rain in your

face,” is one I remember verbatim.

A nurse turned up around 7 p.m., an older woman who

carried an air of competence, authority, and goodwill. Darcy’s focus seemed

unblunted as she began describing the tests he’d been given, and he cut her

short—“What’s wrong with me?”

“We’re going to have to admit you. You’ll talk to the

oncologist on Monday, but right now—maybe you’d like your friend to leave while

we go over the results in privacy.”

“He can stay.”

“We have some

serious information to go over here, is why I suggest

—”

“Then go over it, okay? My friend can stay. What’s going on here?

What is happening to me?”

“The cancer in your lungs

has spread, and we’re seeing tumors in your brain. A whole lot of tumors, Mr.

Miller.”

“Cancer in my lungs? What cancer?”

“Were you not aware you have Stage Four lung

cancer?” “I guess I am now. And brain tumors—is that cancer too?”

“Yes. The lung cancer has

metastasized. The condition is very advanced.”

“So this is the end.”

“This is metastatic cancer, Mr. Miller,

yes.” “How long? And please don’t shit me.”

“You can ask the doctor about that. Monday,

the oncologist—” “Nurses know more than doctors.”

She looked at me, and then again at Darcy, and then paid

us both, I believe, a great compliment by her candor: “A month. A few weeks at

the most. But probably not even a month.”

Silence while she held Darcy’s hand. After a few minutes

she left us without a word.

Darcy went on staring upward. I must say, he had the

kind of stoic poise I’ve always felt, personally, would lie far beyond my own

reach in such straits. I had no idea what thoughts might be tumbling among the

tumors

in his head until he frowned at me and said, “Well, hell…I might’ve known. It

was Andy Hedges all along, the whole time, from the start to the finish. Andy

Hedges.”

“Who’s Andy Hedges?”

His chest ballooned, and he heaved a sigh. Then—“What?” “Who’s Andy Hedges?”

“I don’t know.”

Long after night had fallen, Darcy was wheeled on his

gurney into an elevator to be taken to a private room. As he traveled, he was

sleeping. I tagged along as far as the doors to the elevator. He was still

unconscious as I wished him well. The doors closed, and I didn’t see him again

ever. He became the charge of Jerry Sizemore, who arrived in Austin late the

following afternoon. I left Austin on a plane that morning, and Jerry and I

didn’t quite overlap. These long years later, I still haven’t met Jerry Sizemore

in the flesh.

Darcy died on the twelfth of June, exactly one month

from the time he was admitted to the Parkland Community Hospital and the nurse

with the kind face and sincere touch held his hand and predicted that very

outcome. Jerry Sizemore, I guess, would have been the one to see to Darcy’s

affairs and effects, which in the course of Darcy’s travels had bled away to nothing. Here in

Northern California fifteen years later, in this house where Link has died and

where I’ve stayed on—not only out of exhaustion but also because I’ve grown

stuck in my role, it’s become my religion to carry things to and fro in the

temple, and I find no reason to adjust right away to the demise of our god—here

in this house not haunted, but saturated through-and-through with the life of

its dead owner, it falls to me to sort through Link’s aggregations of rocks,

bricks, broken seashells, tools, books, medicines and medical supplies,

firewood, driftwood, lumber, cartons of Quaker Oatmeal, cases of Ensure

meal-supplement drink, frozen foods dating back, at least in one of his

freezers, eighteen years to 1997, smashed appliances, exploded vehicles,

incomplete, irrelevant, or incomprehensible documents, and “parts”—that is,

agglomerated nuts, bolts, shafts, gears, belts, bearings, all on their way from

rust to dust— and small, delicate, though casually handled boxes holding the

memorabilia

we call “odds and ends” because their attachment to any human personality has

been annihilated: an old tintype portrait of a darkly wooden face neither male

nor female, an acorn encased in a cube of clear Plexiglas, medallions and

badges in plastic envelopes, other such things—a snow globe, its surface so

worn you can’t see what it holds, but by its heft you know the water still submerses

the wintry scene inside, while nobody who ever beheld it remains alive.

I came across a scarf among Link’s things, a gift he’d

intended for Elizabeth, his former wife, a yellow silk scarf folded up in soft

white paper and laid in a small red box with a card bearing two words—

For Liz

Liz was the only woman Link had truly loved, he confided

in me many times, as his body and mind failed him in his deranged bedroom with

the dangerous wood-burning stove surrounded by the tottering stacks of

flammable publications…I often observed him lying in bed, holding his cellphone

in one hand and in the other a can of charcoal- lighting fluid—his little trick

was to stretch his long left leg out and hook the stove’s door handle by his

toe, flick it open with a simian flair, and train an incendiary stream into the

flames within to produce a small-scale explosion followed by five minutes of

hard, bright burning (poor circulation gave him cold extremities), meanwhile

yacking on the phone with Liz, who lived in San Mateo a hundred miles away. She

and Link had been married and parted decades before.

The daughter of Japanese immigrants, Liz, a black-haired

beauty even now in her sixties, had become in recent years a physically quite

tentative and cautious person, with a ceremonious, exploratory footstep,

because she no longer had any idea where she was going or where she’d been as

recently as two seconds ago, her memory and identity wiped away by Alzheimer’s

disease. But she stayed serene and cheerful, and greeted everyone, whether a

lifelong acquaintance or a brand-new face, with a hug and a smile, saying,

“Hello, stranger.”

Of the scores of

family and friends who adored and supported Liz—

in

fact, of all the human beings in the world—Link was the only person she

recognized. And in this world, which is only Now, she knows him perfectly, as if

they’ve just risen from their custom-made king-plus- size waterbed—have I

mentioned he was six foot nine, a sliver over two meters tall?—the two of them

beautiful and young, and rich from his many business enterprises. Liz doesn’t

know her husband Malcolm, a retired U.S. naval captain who sees to her every

need and even calls Link’s telephone number for her nightly; and nightly Liz

and Link talk on the phone and she pledges her love, and Link, who has never

for a minute considered, in his own heart and mind, the marriage ended, drinks

in these declarations and answers them with his own in the midst of a world

without forward or backward, without logic, like the world of dreams, thanks to

Liz’s dementia and to Link’s opiated vagueness and diabetic spikes in blood

sugar, his occasional insulin psychosis, and the cycles of delirium driven by

the ebb and flow of toxins, mainly ammonia, in his bloodstream.

Liz rarely left her own home in San Mateo, but Malcolm

was willing to bring her north for a visit. She knew Link’s voice, and we hoped

she would recognize Link’s face too, though they hadn’t been physically present

to one another for many years. Link vowed to me he would live to see Liz again.

Liz, of course, had no idea any of this was being considered. Because taking

her places was a matter requiring a lot of care and strategy—and time—Link was

forced to count the days and hang on.

For more than a week at the start of April, while he lay

finally unable to leave his bed, stretched out to his full six feet nine inches

diagonally across his mattress with his orange tomcat Friedrich asleep on his

chest, a succession of storms, three of them, all of tropical origin, had swept

in from the ocean to do violence, and now a fourth disturbance, not the worst

of the crop, but impressive enough, had the crowns of the hundred-foot redwoods

churning in the gulley behind the house. At least a couple of times each day

the house lost electric power, and in the chair by the stove I would have to

stop reading my book and listen to Link and his cat snoring between thunderclaps.

In the middle of

one of these outages, about three in the afternoon,

Link

called me to his bedside and demanded to be brought to his room. I told him

that’s where we were—in his room.

“It looks like

my room,” he said, “but this is not my room.”

Link…except for the eyes peering out of his hairless

skull he looked no different than a corpse, but his thoughts were alive. And he

wasn’t always appropriately oriented. You had to be careful with him.

“What does your

room look like?”

“It looks a lot like this one, but this room isn’t the

right room. Do you understand? This is not my

room.”

“So—you want to

go to your room.”

He saw I didn’t get it. As if translating each phrase

for me into my hopeless foreigner’s tongue, he then said: “I wish…to proceed…to

the chamber…which is mine.”

“First of all,” I said, “I don’t know where you want to

go. Second of all, there’s nobody here but me. How am I going to get you on

your feet all by myself?”

As if gravity had been revoked, he rose to his full

height and took three strides to the sliding doors of his bedroom.

“Link. Link.

Where are you going?”

With a sweep of his arm he pushed aside the glass pane,

and the outdoors rolled into the room. He stood for a few seconds with the rain spitting in his face, then stepped

into the storm.

Should you ask—it never occurred to me to prevent him. I

followed him into the dark afternoon. He stood swaying in the yard, which

sloped gently for a hundred feet before plunging into the mile-long gulley that

ran down toward the ocean, or rather down toward the roaring extinction into

which ocean, earth, and sky had disappeared. For a moment Link took the measure

of something, perhaps of this shot of strength he’d received, then like a

performer on stilts he set his distant feet walking, steering himself through

three kinds of thunder, that of the gusting wind, that of the drunken ocean,

and the thunderclaps following the lightning. I described the redwoods as

churning, but their motion better resembled a towering shrug—in a storm the

redwoods seem to me punished, resigned, while the cypress

trees

seem out of their minds, throwing their limbs around hysterically. As I trailed

Link closely through this flickering chaos, he in a Peruvian herder’s cap,

pajama bottoms, barefoot, barechested under a long ragged bathrobe open and

flapping in the gusts, it seemed to me inescapable that he meant to

stumble-march down into the gulley, the sopping brambles and tangles, the

thunder, the sea’s embrace, and never come back. I was mistaken. He soon banked

left, and circled around the corner of the house to balance in front of his

bedroom’s back door—situated about sixteen feet diagonally across this bedroom

from the sliding doors he’d walked out of. The journey had covered thirty or

forty paces and lasted under ninety seconds. The weather was more wind than rain—Link

was spattered, but not soaked, as he sloughed off his robe, lay down in bed,

thanked me for my help in getting him to his proper room, and immediately began

dying.

Until the consummate couple of hours, Link was able to

hear me and talk to me. I asked him if I should kill him with the morphine, and

he said no. He preferred to wrestle with his torment, sitting up in bed,

pivoting right and left, putting his feet on the floor, hunching over and

rocking, curling into a ball, straightening out on the bed, lying east, lying

west, no position bearable for more than a few seconds—more active in this

single afternoon than I’d seen him in the last two months put together—and he

wanted no help with this. As Link understood it, the doctrine of his spiritual

teacher nine thousand miles away in India required him to live each incarnation

to the last natural breath, which came for him about nine o’clock that night in

a long, gently vocal sigh. But before that, around seven, he spoke to me for

the first time in an hour or so—“Is Liz coming?” “I think she was coming about

eight,” I said. “What are you doing?” he asked me—“sitting shiva?”—his last

words. His fight gave out and for the rest of it he lay on his back breathing

like a sump pump with lengthy stops and convulsive, snorting resumptions,

terrible to listen to, but only at first, and after that a sort of comfort.

An hour into this phase, almost exactly at 8 p.m., Liz

arrived. She entered Link’s bedroom by the back door, as mindful as a tightrope

walker,

measuring her steps against the void, assisted by her husband Malcolm. As

Malcolm continued through the kitchen to join me in the dining room, Liz went

down on her knees at the bedside with her arms stretched out straight across

Link’s breast, her face pressed into the mattress.

Malcolm sat beside me at the cluttered dining table,

some distance from the bedroom but with an angle of view on his wife. Even here

on the other side of the house, and despite the dull booming of the weather all

around, we could hear Link’s respiratory system at work. In the high winds the

house seemed similarly unconscious but alive, the walls and windowpanes

trembling. Malcolm had gone to generous lengths in order to get Liz here for

this last meeting and parting with Link, just as he not only enabled but

encouraged their telephone conversations, pressing himself into these services

out of some poetic inkling, I’m willing to assume, some unbearable intuition of

the rightness and even the beauty of the facts. He had a round, clean face

drained long ago of any sadness or happiness. We sat side by side and said

nothing, did nothing.

After forty-five minutes, Malcolm left me and entered

the bedroom. Liz stood up and said, “Night-night, Linkie. I love you.” She

turned to embrace her husband of twenty-five years and said, “Hello, stranger,”

and they went out the door. I heard their car pull away, and ten minutes after that Link was dead. The storm continued till about 3

a.m. while I sat by the stove and while the cat Friedrich, made stark

in the flashes of lightning, marched restlessly over the boxes and bags and

piles. There was nothing to be done. I didn’t want to trouble the hospice staff

or the mortuary people until morning, and there was no one else to call. As

with Darcy Miller at the end, so with Link—down to a couple of friends.

In the last decade and a half I’ve corresponded a bit

with Jerry Sizemore, but he hasn’t volunteered to tell me about Darcy Miller’s

last days, and I haven’t invited him to. I understand, however, that Jerry

Sizemore sat at Darcy’s bedside every day, all day, for thirty-one days, until

Darcy took his final breath.

I got that story

from Mrs. Exroy. I encountered her now and again

during

the next few years, over the course of which I got back to Austin several times

to teach as a guest professor, and whenever I ran into Mrs. Exroy, usually

while she stood smoking an extra-long filtered cigarette behind the Brewer

House, flicking her sparks and ashes into the ravine, Darcy Miller’s death was

the first topic of our conversation, and she described for me each time, as if

for the first time, Jerry’s faithful attendance at his friend’s bedside those

last thirty-one days. Then after four or five years Mrs. Exroy and I stopped

bumping into each other, because she died too. Oh—and just a few weeks ago in

Marin County my friend Nan, Robert’s widow—if you recall my shocking phone call

with Nan at the very top of this account—took sick and passed away. It doesn’t

matter. The world keeps turning. It’s plain to you that at the time I write

this, I’m not dead. But maybe by the time you read it.

1 comment:

Thanks for sharing this! I’m delighted with this information, where such important moments are captured. All the best!

Post a Comment